IASLonline NetArt: Theory

Thomas Dreher

Pervasive Games: Interfaces, Strategies and Moves

- Abstract

- "Interconnectedness" and Mobile Devices

- "Pervasive Game" as Generic Term and Special Form

- "Magic Circle" – a Questionable Leading Term

- A Definition of the Term "Interface"

- Endophysics: The World as an Interface

- World-Interface (Interface 1)

- Game-Interface (Interface 2)

- Game-oriented World-Interface (Interface 3)

- From the Game to the Gamer´s Move

- Examples 1: Games with Virtual Spaces

- Examples 2: Games with Camera Phones

- Examples 3: Hotspot-Hunting

- Types of Mediation of (Levels of) Interfaces

The terms "immersion" and "magic circle" are transferred from the discourse on computer games to theories of pervasive games. The reuse of these terms in a new context leads to contradicting arguments. An interface model is proposed as an alternative: A 'game-oriented world-interface' mediates a 'world-interface' with a 'game-interface'. The 'world-interface' is constituted by the bodily and cognitive access of the gamer to the world. This method is oriented to the gamer and her/his actions. The 'game-oriented world-interface' substitutes the opposition between the reality as a playground and the game system by the participant´s orientation to the game strategy and the environment.

Pervasive Games are one of the media forms documenting "the increased interconnectedness of our communication systems". Instead of being "distinct identities" 1, new media forms are constructions combining existing technical facilities (servers, antennas for the mobile telephone system, satellites for GPS) and connections (telecommunications, mobile telephony) with terminals delivering additional functionality. These constructions are made possible by contemporary communication systems.

Important properties of the "interconnectedness" include:

These properties characterise, for example, network projects that offer participants functionality to localize media and content (texts, photos, films and audio files) on maps. These projects combine locative media (geodata), databases and photos of satellites (maps) as a geographic system with databases for the input of location-based information.

The above-mentioned properties characterise pervasive games with mobile equipment for participants mostly playing in an urban context. 3 Pervasive games combine gamers, rules and the actual forms of the "interconnectedness of our communication systems" in different manners. Participants use their anticipations of possible environmental situations to develop strategies for the combination of the game´s rules with their use of mobile devices in moves. 'Moves' are executions of game plans in actions based on the body coordination and the orientation in environments (see chapter "Game-oriented World-Interface").

Players of computer games become immersed in a fictional world by the three-dimensional animation. Technical interfaces (keyboard, mouse, game console, monitor) offer means to enter this world. Under the heading term 'immersion' scientific scholars of computer game studies discuss the localisation of the player either between the technical interface and the simulated game´s world or exclusively in the game´s world. In the last case, (s)he doesn´t perceive consciously the interface although moving on and with it. (S)he moves within the animated game space without any necessity to concentrate her-/himself on the coordination of body actions while acting on the devices. 4

Pervasive Games replace the immersion of the player in computer games with a plurality of technical and human interfaces (cognition with body coordination). In pervasive games the screens of terminals take over diagrammatic functions of the score´s indication. The use of the mobile terminals under the game´s requirements demands strategic capabilities as well as wit in the environmental orientation and body coordination. The immersion of computer games is replaced by constructions of game strategies for the realization of moves under the game´s requirements. Pervasive games substitute the immersion in computer games´ worlds by corporeal-cognitive operations coordinating the use of mobile devices with the orientation and body coordination in environments.

The term "pervasive games" is used as a generic term for "augmented reality games", "ubiquitous computing games" and location based "mobile games". These modes of games are realized by participants in locomotions with mobile devices.

Likewise the term "pervasive games" designates a special form: It is used for games, too, with participants moving with mobile devices (laptop, PDA, mobile phone, GPS, digital camera, RFID) in real environments. The devices of different players can be connected with each other via mobile telephony and internet. The locations of the gamers and their moves to other places are a component of the game process not only in systems with locative media but in projects without these media, too (location based "mobile games", "location based games").

Head mounted displays are utilized in "augmented reality games" as simulation technologies. The displays are placed before the eyes and project virtual elements into the view of the real world. Participants moving with head mounted displays in a surrounding area regard virtual and real elements on one level of observation but the game process can provoke the necessity of the distinction between simulated signs of the game and tight elements of the real space bound to gravity.

Although the term "ubiquitous computing" is often used as an equivalent to the term "pervasive computing", Jane McGonigal proposes to differentiate between procedures of localisation making possible digital processes everywhere – "ubiquitous" – , and localisations executable in "pervasive" systems in certain places. 5 "Ubiquitous computing games" offer participants opportunities to play everywhere (via mobile telephony and/or internet access) meanwhile their real places and moves to other places are coordinated by the game system with virtual places and moves. Contrary to that, the game process is constituted in "pervasive games" (as a special form) by actions between real places. Only certain geographic coordinates and/or executable actions take on functions as part of a pervasive game´s (as a special form) process.

"Alternate reality games" are "massive puzzle games" utilizing components presented to players in different fields of media in regular and irregular time intervals. 6 The character as game is hidden or denied. This "pervasiveness" combining temporal and medial variable messages about the game process has another structure as in "pervasive games" (as a generic term). The "pervasiveness" of "alternate reality games" will be left aside in the following. 7

The term "pervasive games in a wider sense" won´t be used below as a generic term for the gaming procedures and the technologies mentioned above because it is bulky. The term "pervasive game" without addition stands in the following for its use as a generic term allowing to mark a difference to "pervasive games in a narrower sense" as a designation of the special form. 8

The "magic circle" (see below) is put in the centre of the argumentation in articles on pervasive games discussing generalisable aspects of the (inter-)medium. A critical review of the approaches to pervasive games shall show up the problems of a method to integrate the gamer´s moves in environments afterwards into theories of the computer game´s closed systems instead of constructing a theoretical framework using the gamer´s orientations and situated actions as fundamentals. The interface model proposed below takes the operations of observation (knowledge) and the operations of observers (action) in the game process as the starting point of an investigation of pervasive games.

In "Rules of Play: Game Design Fundamentals", Katie Salen and Eric Zimmerman go back to the "study of the play element in culture" as it was presented by Johan Huizinga in his book "Homo Ludens". There the authors find the criteria for an investigation of games. Plays and games separate the playground from its surrounding. Plays and games constitute their own worlds within the world with rules only for a limited time space but in a repeatable form: "...the term [magic circle] is used here as shorthand for the idea of a special place in time and space created by a game." 9 For Salen and Zimmerman this "magic circle", as it is marked by organisers of plays as well as of systems of computer games and is marking limits to players as well as gamers, is scrutinised but not broken by alternate reality games und live-action role-playing games.

This challenge of the "magic circle" by transgressions of its limits is lead back to the transgressed by "metacommunication", as Salen and Zimmerman argue refering to Gregory Bateson´s "theory of play". 10 Bateson ventilates the communication between humans with signals. Meanings are assigned to signals against the backdrop of "the discrimination between 'play' and 'non-play'". Bateson explains the communication with signals in plays as a manner of dealing with paradoxes allowing no other solution than the tentative use of "psychological frames" by the communicating actresses/actors. The signals can be interpreted as messages in the contexts of play or non-play: "map" and "territory" as well as play and non-play offer semantic fields for the same signals in a "paradoxical premise system." The player discriminates between these semantic fields: He "draw[s] a line between...messages of the frame-setting type". 11

Salen and Zimmerman feature the "magic circle" on one side as broken far enough to provoke "metacommunication" on the frames. 12 On the other side the "magic circle" is restored by "metacommunication" because the distinction between "play" and "non-play" marked by "frames" within the "game" is conserved against threats: "...the magic circle never entirely vanished." Otherwise "we probably would not be able to call them games." 13 Salen and Zimmerman don´t explicate the combination of magic with reflexion or rather the combination of the play´s fascinating effects (Huizinga) with the choice of an "imaginary line" (as the cognitive operation to mark a distinction). How fit the magic effects on participants to their operations of selecting, (re-)constructing and restoring the threatened play frame?

Markus Montola defines in "Exploring the Edge of the Magic Circle": "Pervasive game is a game that has one or more salient features that expand the contractual magic circle of play socially, spatially or temporally." Montola describes pervasive games not only as expansions of the "magic circle" but also as its infringement: "Pervasive games consciously exploit the ambiguity of expanding beyond the basic boundaries of the contractual magic circle." 14

In Montola´s characterisation the pervasive games demand simultaneously closedness in the sense of the "magic circle" and openness. He states: "...pervasive game is a novel form of gaming." 15 Expansions would be able to open the "magic circle" to environmental conditions but why shouldn´t it then loose its magic based – following Huizinga – on closedness? Montola outlines the problem in a jumpy arguing manner but he doesn´t solve it.

Jane McGonigal modifies Montola´s core thesis about pervasive games in her dissertation "This Might Be a Game": "...it acknowledges the magic circle and then defies it." 16 Even Dakota Reese Brown is responsive to Montola´s proposition on the relation between the "magic circle" and pervasive games. In "Pervasive Games Are Not A Genre!" she suggests a "dynamic synthesis between two objects in conflict": The found playground – "the real world" – and "the magic circle" have a dialectic relationship. Their mediation constitutes "a new singular thesis". 17 Why pervasive gaming has to be first separated from "the real world" and then mediated with it? The theories on pervasive games by Montola, McGonigal and Brown 18 omit some central aspects because first they follow the integration of ethnological play research in theories on computer games and second they modify these theories of closed game systems for games in surroundings. My central thesis is: Abandonment of the confines caused by the reuse of game research concepts based on the "magic circle".

Eva Nieuwdorp and Bo Walther Kampmann discuss pervasive games from the perspectives of gamers and their actions. In their articles they anticipate some aspects of the interface model presented below.

Eva Nieuwdorp is presented beyond the up to now followed chronological order of articles on the theme because she is able to anticipate further steps with her use of the term interface although she embeds her proposition in the framework of the discourse on the "magic circle". In "The Pervasive Interface: Tracing the Magic Circle" she proposes a concept of the interface for pervasive games refering "less to the computer or the user, but more so to the social and spatial environment the interaction takes place in". 19 The concept of the interface proposed below thematizes the observer´s interface to the world as her/his only access to the world and therefore as constitutive for her/his concept of the world (see the chapter "Endophysics"). The relationships between the gamer´s actions, the "environment" and "interaction" can be redefined on the corporeal-cognitive interface of the gamer to the world.

Unfortunately, Nieuwdorp restricts her research by her definition of pervasive games firstly on games establishing a virtual world and secondly on autonomous games´ worlds. 20 In Nieuwdorp´s concept the everyday world changes its meanings meanwhile gaming – but that must not be the case. Why shall the everyday world always appear to the gamer in other points of view than the usual changes in perspective and adumbrations? Huizinga pointed to the demarcation between the everyday life and the play as a precondition of the `magic´ attracting effects of plays, and Nieuwdorp saves her concept interpreting pervasive games as "magic circle" with the help of the assumption about the changes of the actions´ meanings within the game.

Nieuwdorp describes the transgression from non-play to play as "liminal interface". She splits the "liminal interface" into a twofold passage: from the "paratelic interface" (1) to the "paraludic interface" (2). 21 This grading from the everyday life to the "play" (1) and from there to the "game" (2) doesn´t solve the problem of the "magic circle" caused by the influence of traffic situations on the participants´ moves infringing the game´s autonomy: The perspective of the game as a system embedded in real surroundings, meanwhile it segregates itself from the environment, stems in Nieuworp´s article from theories on pervasive games based on the "magic circle" 22, too, and leads unfortunately again to a limited and deformed characterisation of pervasive games.

Nieuwdorp takes the twofold passage from the everyday life first to the "play" and second to the "game" from Bo Kampmann Walther´s approach to computer games and integrates it into her theory on pervasive games. Walther defines "play...as an open-ended territory in which make-believe and world-building are crucial factors." "Game" presupposes the delimited playground: "Games are confined areas that challenge the interpretation and optimizing of rules and tactics..." 23

In the same year as Nieuworp´s above mentioned article was published Walther presents in "Atomic Actions – Molecular Experience: Theory of Pervasive Games" a new theory. In his characterisation of pervasive games Walther doesn´t fall back neither on his approach to computer games nor on the term "magic circle", quite contrary to Nieuwdorp. His model of triadic relations between "tangibility space", "accessibility space" and "information embedded space" 24 suffers from his too cursory explanation of the term "accessibility space". Its position between the terms "tangibility space" and "information embedded space" can only be guessed. Which functions the "accessibility space" takes over in its position between "tangibility space" and "information embedded space"? Are these functions exclusively technical or can they designate aspects relevant either simultaneously or exclusively from the gamer´s perspective?

Walther restricts the breadth of pervasive games to closed and mostly technically prepared playgrounds embedding a virtual level into the real surrounding. The proposal of an interface model presented below can´t be applied only to pervasive games with rules technically implemented in an "input-output engine". Walther´s construction of "triadic space structures" 25 is tailor-made for this "engine". The interface model explained in the following chapters substitutes this triadic structure by another more comprehensive one for pervasive games.

In "Pervasive Game Play: Theoretical Reflections and Classifications" 26 Walther underlines the closedness of pervasive games obtained by the technical equipment and the rules of the game. He distincts from that the openness for changing environmental conditions stressing the gamer´s capability for adjustments. Now Walther uses the term "magic circle" for criteria of closedness, too, refering to Salen and Zimmerman (see above). But: Firstly closedness alone is not a sufficient reason for a 'magic attraction' featured by Huizinga as a characteristic effect of plays. Closedness demonstrates only that a precondition for a system is given. Secondly the relations between openness and closedness are more complex if the focus on pervasive games is not restricted to integrations of technical elements into a delimited playground and to digital systems implementing all rules of the game as Walther argues here again. An alignment to moves in surroundings and to their presupposition, the gamer´s orientation and body coordination, is more fruitful. Then the focus is not only oriented on the closed system´s openness for environmental conditions but is directed to a reconstruction of the game process using participants´ actions in partially changing environmental conditions (see chapter "Game-oriented World-Interface").

The immersion in computer games (see chapter "Interconnectedness" with annotation 4) is substituted in pervasive games by a play with technical (and cognitive-corporeal, see chapter "Game-orientierted World-Interface") interfaces in environmental conditions. As a consequence of his characterisation of the game process as "'immersion' and 'flow'" Walther describes the player of pervasive games as a person actively holding up the game process and avoiding interruptions caused by environmental conditions : "...the mission is to keep on playing..." This player doesn´t imagine her-/himself in a game´s world beyond reality but "'real' problems...remain, well, real problems." 27 This quote demonstrates Walther´s understanding of moves in pervasive games as part of the everyday dealings with environmental conditions, contrary to Eva Nieuwdorp (see above on the change of meanings of the everyday life in pervasive games). Walther describes interference factors as "real problems" like hindering passengers and the social norm as an imperative not to race against their bodies although it will be an advantage for the gaming procedure. But these are only partial aspects of an everyday practice relevant for the game process. Orientation and the body coordination in moves are fundamental elements of acting in environmental influenced normal conditions as well as in game conditions (see chapter "World-Interface", "Game-oriented World-Interface").

Players are able to keep up their concentration on the prevention of possible intersections in passages of time without events promising 'suspense' but with the possibility of occurrences provoking fast reactions. In the gaming procedure a 'suspense' can arise directed by the gamer´s consciousness in situations demanding to act out strategies in moves and to keep up the concentration to prevent dangers. This has not very much in common with 'magic' or 'infecting' actions. Immersion, dynamics of play ("flow") and "magic circle" are not adequate terms for moves in pervasive games: The players keep up again and again the gaming procedure without being immersed into a game´s world and without being directed so specifically by demands implicit in a game´s structure and its process ("flow") as it is the case in computer games.

Walther presents his explanation of the term "gameplay" in "Pervasive Ludology: Play-Mode and Game-Mode" not only as valid for processes and moves in video and computer games but for pervasive games, too. The first one of his both definitions of the "gameplay" marks its meaning in a manner overlapping the meanings of the terms 'strategy' and 'move' as they are used here. Walther emphasises in his second definition of the term "gameplay" the "asymmetrical relation between world exploration and level progression." 28 For Walther, the reference to the world is defined by a.) the making of the difference play/non-play within the game, caused for the gamer by the non ignorable elements of the real, and b.) the situationally conditioned game progress. The process of a game has to be unfolded by players only seldom as a "level progression" but on many occasions as a query in and of the surrounding often in not longer enduring lapses of time. In Walther´s actual theory the game´s ascent in complexity from the "play" to the "level progression" is compelling but pervasive games contradict it 29: They are often in a more complex manner integrated into surroundings and have a more simple structured gaming procedure.

Walther´s conclusion is ambivalent: "...traditional video games may have moved" with pervasive games "out into the real (urban) world. Yet, games remain games." 30 This can be read as if Walther annihilates his model of two levels (firstly "world exploration", secondly "level progression") in favour of one game level ("games remain games") and openness will again endanger closedness.

All presented theories on pervasive games hark back to theories developed for plays and computer games. Either the authors have not been able until today to fulfill the aim of a sufficiently broad theory adequate for different kinds of pervasive games, or the problem has to be found in the procedure of adaptation causing the loss of important aspects. The interface model offers a restart.

Nils Röller and Siegfried Zielinski distinguish in "On the Difficulty to Think Twofold in One" the etymological meaning of the term "interface" in English and German. In German "interface" means a region between different realities or levels of reality not offering possibilities for sojourns. In English "interface" stands out for "the meeting of two faces/surfaces". Webster´s Collegiate Dictionary defines "meeting" as "the place at which independent and often unrelated systems meet and act on or communicate with each other."

This 'meeting place' is a turning point for a switch from one to the other. The switch can be made like a plug or an adapter (hardware), but it can be effected as a translation (as in software), too. The forms of the switch on the one hand as compatible elements not allowing sojourns and on the other hand as designed fields for functions organizing translations are combinable – like the combination of hardware for transits and software for translations from one system to others.

The interface is a 'connecting form' ("Passform") and/or a configurable 'seam' ("Nahtstelle"): The first allows no sojourns contrary to the last one. Heart rate analysers and locative media convert the data of the gamer´s actual state and location allowing her/him to influence the effects of these data for the game process only by moving her/his body and changing her/his location: The player behaves following criteria how her/his moves 'fit' into the system of the game. But the technical interfaces of mobile devices offer 'opportunities for sojourns' to the gamer for inputs without the necessity to move her-/himself: (S)he is able to effect changes by using the interface as 'seam'. Body movements with changes of locations and the handling of the technical equipment are the fundamentals of strategies fixed on the game´s finish: Systems´ reactions can be provoked by gamers acting and changing locations and/or inputs.

Reactive installations thematise the human computer interface design and, with it, the dispute on the interface as a machine and its function as prothesis as well as an apparatus influencing the formation of interaction patterns. This theme is of lesser interest for the present state of pervasive games´ development. Interaction patterns (as capabilities for the use of equipment) open for modifications are presupposed as gamers´ abilities but not problematized, different to some reactive installations. 31 Nevertheless cognitive-bodily and technical interfaces are matters of interest for a discourse on pervasive games as the following interface model demonstrates.

Players correlate their manners to orientate themselves in a surrounding and to move their body with the rules and the technical equipment of a pervasive game. The participants develop strategies for this coordination and realise them in moves. The interface model uses a reconstruction of the relation human – environment as a basis to build upon it a framework for strategies and moves with mobile devices in surroundings.

In his theory of endophysics Otto E. Rössler outlines the observer as a part of the world. If world and observer contort parallel then the world doesn´t change for the observer because the relations between her-/himself and the world remain constant ("codistortion"). Changes of the world not recognizable for the "internal observer" may be observable from an exophysical point of view comparable to god. The consequences of the "Boscovich covariance" 32 for physics – for example 'how to construct interfaces for internal observers allowing conclusions on the relation endo-/exo-physics' – are not relevant for the interface model for pervasive games, contrary to the impact on the relation of the observer to the world.

The observer at the "endo-interface" to the world doesn´t recognize if (s)he or the world are changing but recognizes changes on the interface: "...the world is necessarily defined only on the interface between the observer and the rest of the universe." 33 On one side the interface is a switch (see chapter "A Definition of the Term 'Interface'") between the observer´s inner world (cognition, proprioception, sensomotoric system) and her/his outerworld (fields of activity, interaction), on the other side the observable world can be defined only meanwhile the realisation of the switch: We observe the world but we don´t receive observer-independent data on this world.

The body coordination and the orientation in surroundings via observing are interlocked on this observer-centered interface: A clear distinction between experiences of the inner- and outerworld is cancelled out by the need of the proprioception for the body coordination in surroundings. There are ways of using the proprioception for the body coordination in surroundings. The interconnection of the inner- and outerworld is the result of the interconnection between body coordination and the orientation in surroundings. A part of the corporeal and cognitive interface capabilities is given. But because of their nature they are not static but offer the preconditions for prereflexive and reflexive actions executable under game conditions. The interface is reconstructable in a neurobiological sense at the interconnection of the inner- and outerworld´s experiences and in an endophysical sense as a model of the observer´s relation to the "rest of the universe".

"Internal observers" (see chapter "Endophysics") recognise the world in activity: They educate themselves to orientate and move in it using and developing "stimulation patterns" 34, "schemes" 35, "turning markers" 36 and other cognitive modes. Modes of orientation and body coordination (schemes for the body and for actions) are fundamentals for actions in the world. The problems posed by the "Boscovich covariance" to physics are left aside in the following contrary to the returning problem of a "world" being "real" meanwhile there is no "recognition of the world possible without interpretation, interaction and intervention." 37

Otto E. Rössler reacts to the problem of the "internal observer" to recognise real changes in the world by the distinction between endo- and exophysics. Following Rössler, a computer-aided construction of a model world with an explicit observer in an endo-world offers the opportunity to reconstruct features of an exo-world. The methodic fundament of the concept of a cognitive 'world-interface' or 'interface 1' presented here is the relation between reality and the observation relative to the point of view in the world as it is thematised in endophysics: The observer-centered objectivity incorporates this relativity (see chapter "Endophysics" with annotation 32). This observer-centered objectivity can be distinguished from an absolute objectivity and a relativism negating objectivity. 38

In the (endo-)world, the "'real'-interactive", in an acting-recognising manner constructed ways of orientation, and body coordination constitute a cognitive-corporeal interface: "an intervention and interaction fabric" ("ein Interventions- und Interaktionsgefüge"). 39 The orientation and the use of the body as well as the use of signs and language are trained simultaneously: The recognition of the surrounding, actions (via body coordination) in it and language acquisition interpenetrate each other.The learning process is as well socially conditioned as it is coined by individual interpretations. Stimulation patterns, schemes and turning markers are constituted in this process of "sign-acting". 40 The knowledge of the surrounding impregnated by interpretations and its biologic foundations constitute the access and the interface to the world.

The "theoryladenness of observation" is a result of the perception and identification of objects, circumstances and movements impossible without patterns and the formation of schemes: Impressions of objects don´t arise immediately in the everyday practice but patterns, schemes and categorizations serve the memory as means for recognition and for orientations. There is no original state before the interplay between the cognition of the world and the observer´s operations within the world via the (orientating) body coordination but there are innate capabilities of body coordination and the orientation made possible by the former 41: The body and the capabilities of an actress/actor to coordinate the body prereflexively (leading parts of the body by the intention of a direction without the need to recall schemes for the body coordination consciously) and reflexively (see chapter "Game-oriented World-Interface" with annotation 42) constitute the 'world-interface' together with the acquired knowledge of the surroundings. The relationship between the formation of schemes and acting (orientation and movement within the world) as well as the observer-centered access to the world are two fundamentals of an interface-theory for the observer´s operations and moves under a game´s conditions.

In pervasive games a player uses her/his manner to orientate her-/himself and to move in the everyday´s surroundings in a heightened attention because (s)he moves her-/himself in sidewalks, streets, places and on the road not only under the usual conditions to cover distance by feets, bike, car or one of the public transport vehicles. (S)he should be able to orientate her-/himself under the specific game conditions caused by the rules, the technical equipment and other players. Players need to try ways to coordinate their normal orientating moves, the goals defined by the rules and their use of mobile technical interfaces by the development of strategies to be able to react simultaneously on all levels, if it will be necessary. The player´s moves consist not only in subsequent accomodations to the circumstances of the gaming procedure. The moves´ fundament is the integration of the 'world-interface' with its individable possibilities of the environmental orientation and the body coordination (see chapter "Game-oriented World-Interface") in strategies for the game.

The 'game-interface' or 'interface 2' is constituted by the game rules. They are either expressed verbally or they are partially and sometimes entirely technically implemented. Pervasive games with completely technically implemented rules permit their players at the human-computer interfaces (HCI) – the mobile devices (laptop, PDA, mobile phone and others) with screens and input components – to explore the technical equipment in the game process without knowledge of its rules because the technical equipment offers only functions within the rules of the game. This kind of games integrates aspects of the 'world-interface' on the one hand only selectively in the digital game system, on the other hand the players are forced to use their 'world-interface' with all its possibilities to supply the system with needed datas only obtainable by actions in the surroundings.

Other pervasive games use the rules as guidelines offering ways to use the technical equipment. Without informations on technically not implemented rules the technical equipment will be nothing else than an arbitrary collection of instruments with unrelated functions.

The 'game-interface' is constituted by ex- and implicit rules regulating goals and permitting ways to reach the goal. Game-related uses of the technical interfaces can be seen as parts of the rules although often nothing else is explained by the text with rules than deviant uses of the devices relevant under the game´s conditions. Nevertheless all functions of the mobile devices can be used in the gaming procedure. Gamers integrate the possibilities of the 'game-interface' into the 'game-oriented world-interface'.

Pervasive games demand players via rules and technical equipment to develop strategies supporting moves with success in sight for expectable environmental conditions. Gamers develop in the course of '(sign-)play-activities' ("Spiel(zeichen)handeln") a 'game-oriented world-interface', respectively an 'interface 3', mediating between 'interface 1' and 'interface 2'. Gamers follow the rules and integrate their body coordination and their orientation ('interface 1') in action plans (see annotation 35) for the realization of strategies supporting moves with technical equipment ('interface 2'). These strategies and the moves for their realizations constitute 'interface 3'.

Dorothée Legrand characterises the relation between body coordination and environmental orientation in the "pre-reflectively bodily self-consciousness" 42 as "self-relative information", or more precisely, as "information about the world relative to the self". 43 Legrand doesn´t suggest an actress/actor constructing a "body image" of her-/himself and projecing it into the surroundings in her/his imagination but explains the pre-reflectively usable ability to coordinate actions in relation to the environmental orientation. The pre-reflective body coordination doesn´t constrain to plan each action consciously, rather it suffices to indicate the direction of a movement. Players directing their attention to technical interfaces of mobile devices meanwhile they are walking have to try for a short time to maintain their body coordination without updates of the orientation. Because the body coordination integrates the environmental orientation for the alignment of the moves´ directions (and vice versa), the player will soon apply her/his attention to the surrounding in cases, too, when the probability to be confronted with dangerous situations is low.

If players of pervasive games have to react to extraordinary demands then they will apply their attention to the combination of the environmental orientation and the body orientation in "sensori-motor integration". In these cases the pre-reflectively coordinated parts of the body are not directed by a reflectively constructed "body image" but the abilities to coordinate oneself are used in a "proprioceptive awareness" in a better targeted way. 44 Meanwhile the game process the corporeal environmental experience ("the 'transparent body'") is expanded by the concentration on the body coordination as a fundamental of the orientation in surroundings ("the 'performance body'"). If gamers move with heightened attention on the relations between the environmental orientation and body coordination then they explore the relation between "the transparent body" and "the performance body". 45 The 'world-interface' can be integrated into the 'game-oriented world-interface' in strategies allowing to act with heightened attention against the distractions caused by the concentration on the technical interfaces.

Situations caused by other players and environmental conditions require moves realized sometimes at a calculatingly slow pace and sometimes sidestepping rapidly. The technical equipment of some pervasive games recognizes characteristics of the gamer´s moves, as for example accelerated or slowed walking, via locative media (for the calculation of speed) or heart rate monitors. The tracked data are integrated into the game by its rules and the technical equipment. In "`Ere by Dragons" and "Wanderer" 46 the 'interface 2' has the capacity to provoke changes in the game process: Technical components react to the player´s moves and provoke a mutual feedback between the equipment and the gamer coordinating actions, respectively between 'interface 2' and 'interface 3'.

Active Ingredient/Lansdown Centre for Electronic Arts und London Institute for Sport and Exercise, Middlesex University, London/Mixed Reality Laboratory, Nottingham Trent University: `Ere by Dragons, since February 2005

In a 'game-oriented world-interface' participants mediate between a 'world-interface' (for actions with schemes for the body coordination and activities) and a 'game-interface'. This "triade" 47 is constituted by the integration, modification and reorganization of the 'interfaces 1' and '2' in 'interface 3': The courses of roads and the traffic are not considered in another way as is usual but with modificated attention and changed selection criteria for stimulation patterns as well as for schemes organizing the coordination of the body and actions.

It depends from the game how many mediating levels the coordination of interfaces requires from players. "Turning markers" (see chapter "World-Interface" with annotation 36) are abstractions simplifying the memory of complex processes. Via "turning markers" trained gamers can prepare mediating levels between strategies, (re-)orientations in the surrounding and body coordination. The structures memorised and compacted in "turning markers" are folded out in difficult situations to simplify the transformation from plans to moves.

Mediations between 'world-' and 'game-interface' are folded in and out in pro- and retentions (in mental forerunning and retracing processes). The prepared strategies can be memorised, selected, adapted and realized in confrontations with present environmental conditions. It depends from the time pressure if participants can recall the game strategy either only in a compacted or in more detailed form.

The interface model with its focus on players, their observations and actions solves a problem of the discourse on pervasive games as the following two quotations from one source demonstrate:

Pervasive games focus on a game play that is embedded in our physical world...

Pervasive games integrate aspects and characteristics of the physical world into the game play. 48

The first formulation puts the emphasis on the game procedure as action in a surrounding meanwhile the second formulation takes into account only those environmental elements having functions as part of the game´s components and rules. The first formulation reduces relations between 'interface 2' and a not divided 'interface 1' to the embedding of the former into reality ("embedded in our physical world"). The second formulation reduces the surrounding to aspects relevant for pervasive games ("aspects and characteristics of the physical world"), as data for technical components and particular rules – as if it could be sufficient for players to concentrate themselves on isolated aspects of the surrounding. The gamer´s moves are not only influenced by environmental conditions directly relevant for the rules and the technical equipment of a pervasive game, but by the indivisible 'world-interface', too.

The 'world-interface' is not the "physical world" but the human access to it. This access determines how we are able to recognize the world and what we can observe (see chapter "Endophysics"). The 'world-interface' offers the capacity to integrate environmental factors, manners of orientation and the body coordination in strategies ('interface 3') anticipating moves as reactions to demands not recognizable as necessary for the use of 'interface 2' but required for movements in surroundings.

'Interface 3' can´t be reduced to the requirements of 'interface 2'; on the contrary, 'interface 3' mediates 'interface 1' in its entirety with 'interface 2' via the gamer and his strategies. The change from the integration of isolated environmental aspects to the individable environmental orientation makes it possible to constitute 'interface 3' in a mediating manner exceeding the "in/extra-game"-aspects of computer games 49 because not only some phases of the game process and some (references to signs for) environmental elements are concerned by correlations, but the entire process of the moves´ coordinations with and by world observation. In 'interface 3' the conditions of the game and the environmental conditions are mediated by the rules´ objectives for the play in environments. 'Interface 3' is constituted by cognitive capabilities of the participants to develop strategies and by their cognitive-corporeal capabilities to realize the strategies in moves.

'Interface 1' is not concerned with reality but with the gamer´s cognition of it and his/her actions in it. It is crucial in 'interface 2' what the gamer can gather as objectives from the demands of the technical equipment and the rules. In 'interface 3' the gamer coordinates these objectives with her/his environmental orientation as well as her/his body coordination and develops strategies for moves. The interface model is concerned with the gamer and her/his actions on all cognitive and corporeal levels.

The following three chapters present the relevancy of the interface model in examples.

Gamers of the MMORPG ("massively multiplayer online role playing game") "BotFighters" of It´s Alive 50 move with mobile phones in the real space to ameliorate their positions compared to opponents on the virtual battle ground. "Botfighters" is "pervasive", not "ubiquitous" (see chapter "Pervasive Game"). The distances between real places are acquired by the identification numbers of the cellular network´s sites ("Cell-ID-positioning technology").

For being able to attack an opponent the gamer has to locate her-/himself in the same cell site. If a gamer wants to escape her/his opponent (s)he has to leave the cell site. Meanwhile the gamers´ positions are real and virtual at once the battle is fought virtually, on the technical interfaces of the mobile phones. The games for different countries (as, for example, Sweden) are structured in episodes.

The screen presentation of the first person shooter indicates only the distances between avatars on a radar screen. The adversaries´ avatars are presented in a virtual setting structured in concentric circles. The gamers have access to a website for the construction and armament of the avatars. The website shows the score and the "robucks" won in the present state of the game´s process. The "robucks" are means to ameliorate the armament.

Itīs Alive: Botfighters 1, since April 2001

The virtual level constitutes a closed system of technically implemented rules. The rules are combined in "BotFighters" with a plot demanding a rebellion against an oppressing regime as task. The gamers take one of the two sides – oppressors or rebels – and receive "missions" via SMS containing informations about places relevant for the game. After the gamers approached each other in the real space the fight can start on the virtual level: The mobile phone is the screen and the battleground at once.

The environmental orientation and the use of means of transportation are skills stressed in the tactical position game not only selectively: The gamer must apply her/his 'world-interface' at full volume. 'Interface 2' consists of the game´s rules for moves in real space and the technical implementation of the fight. The 'game-interface' integrates only locations of the 'world-interface' into the virtual battle ground. 'Interface 3' consists of the sequencing of moves in real spaces to gain fighting positions and the following fights acted out on the technical interface.

Itīs Alive: Botfighters 2, since January 2005

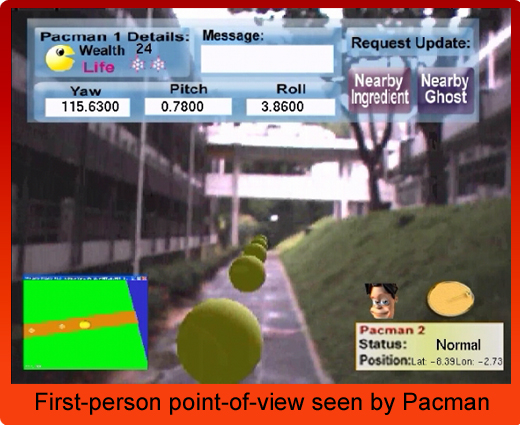

In the augmented reality game "Human Pacman" of the Mixed Reality Lab participants move with semitransparent head-up displays and portable computers on the campus of the National University of Singapore. They adopt the roles of "Pac Men" and "Ghosts" as they are prefigured by the classic Arcade game Pacman (1979). 51 Per game groups of two players and two helpers form a "Pacman" team and a "Ghost" team.

Virtual objects are laid over the head-up-display´s field of view. If players as "PacMen" walk through virtual balls ("cookies") then these balls will be deleted and the score´s amount of points will increase. Furthermore, "PacMen" can 'collect' real objects with integrated Bluetooth emitters. These "special cookies" give "PacMen" forces to catch "Ghosts" for a limited time. "PacMen" must try to catch all "cookies" without being touched by a "Ghost´s" hand on a sensor mounted on their shoulders. Meanwhile, the "Ghosts" try to catch the "PacMen" before they could catch all "cookies".

The helpers survey the game process in the internet-fantasy-game simulation "PacWorld". Players can call up this virtual world on their head-mounted display. Players and helpers communicate with each other via "bidirectional text messaging". The portable computers of the players are connected with the game server via WLAN. The server coordinates "PacWorld" in real time with the simulations projected on the field of view of the head-up display.

The signs of the game superimposed upon the field of vision of the head-up display and signs representing objects of the real world are simulated in "PacWorld" ('interface 2') in 3D as parts of a parallel world with fantasy elements. The environment used as playground is reduced in the simulation to the elements being relevant for the coordination of the game process by the technical equipment: Unpredictable events in the surroundings are disturbing factors changing the game process only in the short term but not in the long term if detours around obstacles will become necessary – "PacWorld" remains the benchmark. The 'game-interface' reduces the 'world-interface' to a model world. In this model world the players appear as virtual play figures repeating the actions of the players in the real world.

The gravity and the vertical axis for the orientation of the body coordination remain for players relevant benchmarks for moves in the real world in game processes, if they use the presentation of "PacWorld" on the head-up display. Real solid objects are circumvented or grasped, if they contain "special cookies", meanwhile the virtual "cookies" must be treated as weightless-immortal elements only located within the animated space.

Mixed Reality Lab: Human Pacman, 2003-2004

"BotFighters" and "Human Pacman" isolate components of the real world in different manners for the mediation with 'interface 2'. In 'interface 3' players must consult their orientation and body coordination in its entirety ('interface 1') for moves complying with the game´s requirements. However the rules of "BotFighters" shape – contrary to the following examples – these moves only indirectly by the game´s goal and not directly by explicit requirements or guidelines to act in surroundings in a specific manner to reach the goal. The players of "Human Pacman" receive – in opposition to "BotFighters" – guidelines how they can adjust 'interface 1' to the game´s goals. After moves in the real space the players of "BotFighters" act in the virtual game space, meanwhile in "Human Pacman" actions in the real and virtual spaces can´t be accomplished as separate sequences. The coordination of 'interface 1' with 'interface 2' demands in "BotFighters" an intense personal contribution in 'interface 1' and for 'interface 2' skills using the technical equipment whereas "Human Pacman" requires these skills coupled with body coordination. In comparison to the next examples the two pervasive games with virtual spaces reduce requirements to develop mediating levels for 'interface 3' by the technical implementation of the rules.

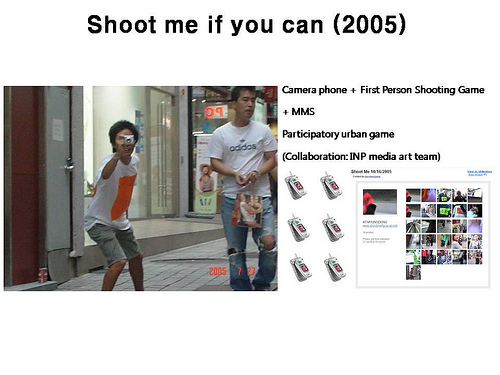

In Taeyoon Choi´s tag game "Shoot Me If You Can" 52 participants walk with camera phones in Seoul and present each other the mobile numbers on coloured stickers mounted on the front and rear side of garments for the upper body. The members of a team try to photograph the members of an opponent team faster as the last ones can photograph the first ones. The participants can act as single players, too, and try to photograph all opponents faster than they can. The winner succeeds in being the first one (the fastest) to fulfill the game´s task.

A server receives the photos via MMS (Multimedia Messaging Service) (shootmegame@gmail.com) and forwards them automatically to Flickr.com. A gamemaster examines a photo being sent via SMS and informs the photographed player by the message "You are shot" if the photo is sharply focused. The game´s website presents the actual score. Participants can receive these informations on their mobile phones.

Only the automatically executed conduct of the received photos from the game´s server to Flickr.com is an own implementation. Apart from that no rules ('interface 2') are technically implemented: The use of the customarily commercially available technical equipment and open networks (including network connections) is predetermined by the rules for "team game" and "run and gun game" presented on the game´s website. But players can specify other rules, too.

In a playground with fixed limits players look for other players to photograph them. The players use obstacles to hide themselves from opponents. Players must try to integrate strategies to prevent being photographed and to seek other players into their environmental orientation ('interface 1' in 'interface 3').

The modifications of the camera phones´ uses (to photograph moving targets sharply enough) under the game´s conditions complement larger modifications of the environmental orientation ('interface 1'), for example to find obstacles just in time or to follow running participants between passersby and cars ('interface 3'). 'Modification' does not contain transformation but changes of goals and the priorities of orientation, body coordination and strategies of the everyday´s practice (for example action schemes).

Players construct 'interface 3' mobilising their environmental orientation and body coordination ('interface 1') to full extent as well as integrating 'interface 2' in it, then containing the prescribed use of mobile devices, the feedbacks of the gamemaster and the score datas. This integration of messages and technical functions into the game process distinguishes "Shoot Me If You Can" from conventional tag games. The environment´s perception (consequences of 'interface 3' for 'interface 1') shifts in "Shoot Me If You Can" in the same manner as in tag games: The attention is directed on possible hiding-places and catch strategies.

Taeyoon Choi: Shoot Me If You Can, ab Juli 2005

The fabric carriers with mobile phone numbers used by players of "Shoot Me If You Can" to indicate themselves are substitued in area/codeīs "Superstar Tokyo" 53 by Japanese Purikura stickers with participants´ pictures and the game´s logo "star". Each player locates ten stickers on easy observable places in the playground. Players photograph their stickers with camera phones being able to read their QR-Codes and send their pictures for the registration to s@mobot.com.

The tag game of "Shoot Me If You Can" is changed to a game of exposing one´s own stickers for being photographed by other players. The photographs are sent to the game´s server. The accounts of the photographers as well as of the stickers´ owners win 100 points with each photograph sent in. Participants are linked. Photographers participate in the distribution of points for all further photographs to the photographed stickers´ owners; photographers receive 25 points lesser than the photographed and linked players receive for their photographing actions. The game´s head quarter affirms via SMS the received amount of points.

"Superstar Tokyo" presupposes a game server for the identification of a "star" sticker, the photos sent in, their links and the distribution of points. The technically implemented awarding of points regulates the cooperation between players.

The hide and tag game of "Shoot Me If You Can" is substituted in "Superstar Tokyo" by a game process allowing to environmental conditions only to hamper the outworking of the (now contrary) demands of 'interface 2' in game strategies ('interface 3') by sight barriers. Only the participants´ cooperation by exposing oneself with stickers or by exposing stickers ('interface 3') and by photographing stickers allows the outworking of the game´s demands ('interface 2') and provokes a new perspective on the surroundings ('interface 1') when looking for places to present stickers. The cooperation contains the rivalry because players try to use the point system for their own advantage in the converse role exchange between the exposition and the photographing of stickers.

Meanwhile the 'interface 3' can be reconstructed in "Shoot Me If You Can" as an embedding of 'interface 2' in 'interface 1' strategically oriented toward the hide and seek, "Superstar Tokyo" establishes an 'interface 2' by the points system´s demands for the cooperation of players directing their moves in surroundings ('interface 1'). The technical demands don´t include guidelines for the cooperation of players while presenting and finding each other: Players must develop possibilities for moves ('interface 3') fulfilling the games´ requirements ('interface 2') in given environmental conditions ('interface 3').

area/code (Lantz, Frank; Slavin, Kevin)/ Kamida (Sharon, Michael; Mellinger, Dan): Superstar Tokyo, September-October 2005

In "Superstar Tokyo" the players combine their reorientations in surroundings with their strategies of cooperation allowing to act out the change of roles/the reciprocity of presenting oneself with sticker and catching sight of stickers in an advantageous manner. Contrary to that, in "Shoot Me If You Can" competing strategies of disappearing and efforts to take something from the opponent despite his counterreactions are crucial factors to provoke in 'interface 3' reorientations of 'interface 1' while seeking hiding possibilities.

In "Noderunner" by Yury Gitman and Carlos J. Gómez de Llarena 54 two teams, both with four persons, look for public places allowing wireless internet access (hotspots). The teams are equipped with laptops (with WLAN card), digitial cameras and money for taxi rides. Photos presenting all participants of a team at the place of the found hotspot are sent together with location data and the name of the network (SSID="Service Set Identifier") to the "noderunner weblog" using the found wireless connection. The acceptation depends on the transfer quality of the hotspot. The team with the highest point score wins.

The technical equipment of "Noderunner" makes it possible to find non-observable functions installed in environments. The hotspots are part of the 'interface 1' but as such they are only recognisable with the means of 'interface 2': Players come to know about environmental properties by technical protheses offered by the 'game-interface'. The integration of 'interface 2' into 'interface 3' serves a new orientation of the strategies for 'interface 1' to move in surroundings or rather to receive new informations on the relation observable/non-observable in surroundings.

Meanwhile head-up displays of "augmented reality games" like "Human Pacman" (see chapter "Examples 1"), "NetAttack" and "Epidemic Menace" 55 lay virtual elements over the perception of real spaces, the reality is 'augmented' for players of "Noderunner" not only in the game´s process but they are able to use the found hotspots after the game, too: Meanwhile in "Noderunner" 'interface 2' and 'interface 3' provide contributions to another access to the world ('interface 1'), in "Human Pacman" 'interface 1' (the participant´s world ´s view through the head-up display) and 'interface 2' (simulated elements projected by the head-up display on the world view) are connected on one projection plane for 'interface 3' (head-up display with augmented reality and its recursion to the virtual "PacWorld").

In "Noderunner" the game process serves to recognize environmental properties and these properties provide the precondition for the game: a growth of knowledge about reality in the form of a game. The discussion of pervasive games using the "magic circle" as an unalterable game dimension (see the chapter "Magic Circle") could try to integrate the players´ growth of the knowledge about reality in "Noderunner" as an add-on or peripheral characteristic – but the recognizability of environmental properties is a precondition of the games´ process.

Gitman, Yury/Gómez de Llarena, Carlos J.: Noderunner, since August 2002

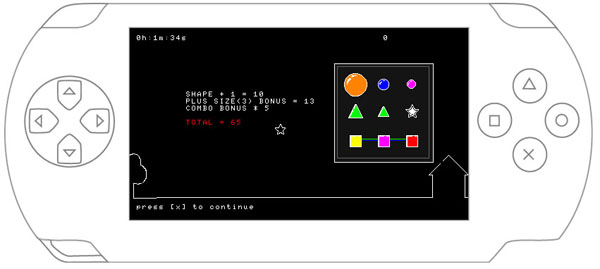

Jonas Hielscher renovates in "CollecTic" 56 the search for hotspots as a game for a mobile playstation (Sony PSP) in a changed mediascape. After having found and stored hotspots with the playstation these data can be used as the context-dependent precondition of a play following the internal rules of a computer game. According to strength and media access control address the hotspots are stored in different seizes, colours and forms. Hielscher programmed the rules of the puzzle defining how the nine signs for found hotspots can be used on a grid with 3x3 squares. One of the tasks for gamers is to try to gain as much lines with the same signs as possible. Hielscher used the PSP software development kit with its collection of "open source tools and libraries".

Gamers build 'interface 3' by developing strategies first for the coordination of 'interface 1' and '2' to detect hotspots and second for the use the playstation´s signets which for one thing represent found hotspots, and, for another thing, are figures in a virtual game ('interface 2').

Jonas Hielscher: CollecTic, September 2006

The aspects relevant in "Noderunner" for a reorientation of 'interface 1' by the detection of unseeable components are once more transfered in "CollecTic" in game-relevant aspects: "CollecTic" shows the possibilities of mobile playstations to use existing local accesses to the internet as game elements. The player is moving but in "CollecTic" as well as in "BotFighters" (s)he does it only to fulfill starting conditions, repectively a first location-dependent period of the game is followed by a second location-independent (or rather location-independent only in its manner to integrate datas of the first phase) period in the manner of computer games. The sequence of periods is coordinated by 'interface 3': 'Interface 1' caters for 'interface 2' via 'interface 3' meanwhile in "Noderunner" 'interface 2' and '3' serve to gain a better knowledge of 'interface 1'.

As a simplifying summary the following seven modes can be indicated as characteristic mediations of interfaces in "pervasive games":

- The technical equipment ('interface 2') functions as means for the transmission and storage of the solutions for tasks. The players (alone or as a team´s member) find the solutions on different locations. The orientation in 'interface 1' is decisive for the game process in its totality but it is modified in moves ('interface 3') with regard to the game´s goal (f.e. "Shoot Me If You Can", see chapter "Examples 2" 57).

- The technical equipment is used for the visualization of certain unseeable features of systems installed in environments (f.e. hotspots). Rules and means ('interface 2') are combined to allow ludic experiences of invisible environmental conditions ('interface 3' serves for the transparency of 'interface 1': f.e. "Noderunner", see chapter "Examples 3").

- 'Interface 2' is a technically implemented system offering players possibilities to construct a relationship network over 'interface 1' (f.e. "Superstar Tokyo", see chapter "Examples 2").

- The environmental orientations ('interface 1') and the mobile technical interfaces with score data ('interface 2') on the one hand are different processes and on the other hand have to be coordinated in moves for example via a sequence system structuring the process in phases (f.e. "BotFighters", see chapter "Examples 1"; "CollecTic", see chapter "Examples 3").

- The environmental orientation is effected by the technical interface ('interface 2') simulating game components (of the environment and virtual parts) in head-up displays and/or 3D-Animation and presenting the actual states of scores. Players can develop game strategies differentiating between real (gravitation-dependent) and simulated (weightless) elements each with other manners of behavior. The conceptualized difference facilitates to control the moves (f.e. "Human Pacman", see chapter "Examples 1").

- The virtual level constitutes an autonomous data space ('interface 2'). The game can be played everywhere. For the coordination of the real ('interface 1') with the virtual level players determine real places (and geodata for storing) for certain virtual game places. The arbitrariness of the connection between real and virtual spaces can be reduced by selecting ('interface 3') a playground with places able to facilitate the game procedure (f.e. "The Journey I" and "II" 58).

- The player is her-/himself the source of data for the technical equipment ('inteface 2') with mobile devices offering informations about the player´s actual body state and/or announcing the consequences of her/his actions for the next moves. The environmental orientation and body coordination in 'interface 1' vary in the game process because the actions of the player´s body must be modified in reactions ('interface 3') to the feedback of the 'interface 2' (f.e. "`Ere by Dragons", "Wanderer", see annotation 46).

Jakl, Andreas Reinhard (Mopius): The Journey I, test project, June 2004/The Journey II, since November 2004

These seven modes of interface connections can be summed up in short features of the relations between 'interface 1' and 'interface 2' as they are coordinated by the 'interface 3' as follows:

- The embedding of 'interface 2' into 'interface 1': "Shoot Me If You Can".

- 'Interface 2' serves 'interface 1' for the recognition of environmental features (functionalization): "Noderunner".

- The relationship network of 'interface 2' over 'interface 1' (hierarchisation): "Superstar Tokyo".

- 'Interface 2' reduces the 'interface 1' to certain informations: "BotFighter", "CollecTic".

- 'Interface 2' reduces 'interface 1' to a model case: "Human Pacman".

- 'Interface 2' needs determinations via 'interface 1': "The Journey".

- Inverse recursions between 'interface 2' and 'interface 1': "`Ere by Dragons", "Wanderer".

'Interface 1´ and 'interface 2' are related to each other in 'interface 3' by embeddings, functionalizations, reductions, hierarchisations, recursions and determinations: This demonstrates the range of mediations between 'interface 1' and 'interface 2'.

Dr. Thomas Dreher

Schwanthalerstr. 158

D-80339 München

Germany.

Homepage with many articles on art (mostly in German), f.e. on Conceptual Art and Intermedia Art.

Copyright © by the author, April 2008 (German version)/October 2008 (as defined in Creative

Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.0 Germany).

This work may be copied in noncommercial contexts if proper credit is

given to the author and IASLonline.

For other permission, please contact IASL

online.

Do you want to comment this contribution or to send us a tip? Then send us an e-mail.

Annotations:

1 Terranova, Tiziana: Network Culture. Politics for the Information Age. London 2004, p.2. back

2 The term 'interface' is used here in two meanings: as a human-computer interface (in the following: 'technical interface') and as human (cognitive and bodily conditioned) interface to the world (see the chapters "Endophysics", "World-Interface" and "Game-oriented World-Interface"). back

3 Examples with descriptions and links in: IASLonline: Lektionen/Lessons in NetArt: Tipps/Tips: Interaktive Stadterfahrung mit digitalen Medien (Internet, Mobiltelefon und Locative Media). Sammeltipp 1: Stadterfahrung mit ortssensitiven Medien (Mapping), Teil 1, Teil 2 und Teil 3 and Sammeltipp 2: Spiele im Stadtraum (Pervasive Games), Teil 1, Teil 2, Teil 3 und Teil 4 (8/27/2008). back

4 "interfaceless interface": Bolter, Jay David/Grusin, Richard: Remediation. Understanding New Media. Cambridge/Massachusetts 1999, p.23. Compare Halbach, Wulf R.: Interfaces. Medien- und kommunikationstheoretische Elemente einer Interface-Theorie. München 1994, p.207-215.

Immersion: Kaura, Ermi/Mäyrä, Frans: Fundamental Components of the Gameplay Experience: Analysing Immersion. In: Castell, Suzanne de/Jenson, Jennifer (ed.): Changing Views: Worlds in Play. Selected Papers of the 2005 DIGRA (Digital Games Research Association)´s Second International Conference. University of Vancouver. Vancouver 2005, p.15-27. URL: http://www.digra.org/ dl/ db/ 06276.41516.pdf (2/9/2008); Salen, Katie/Zimmerman, Eric: Rules of Play. Game Design Fundamentals. Cambridge/Massachusetts 2004, p.450ss.; Schmidt, Florian: Use Your Illusion. Immersion in Parallel Worlds. In: Borries, Friedrich von/Walz, Steffen P./Böttger, Matthias (ed.): Space, Time, Play. Computer Games, Architecture and Urbanism: The Next Level. Basel 2007, p.146-149.

"Situated play" in virtual worlds as well as between technical interfaces and virtual worlds: Rambusch, Jana/Tarja, Susi: Situated Play – Just a Temporary Blip? In: Baba, Akia/Mäyrä, Frans (ed.): Situated Play. Proceedings of DiGRA (Digital Games Research Association) 2007 Conference. The University of Tokyo. Tokyo 2007, p.730-735. URL: http://www.digra.org/ dl/ db/07311.31085.pdf (2/9/2008).

Gamers can treat the technical interface (keyboard, mouse, game console, monitor) like a prosthesis "pre-reflectively" (see annotation 42) coordinated and trained (that is to say as a parallel process of coordination realized without specific attention because the main focus of attention is turned to the game) similar to the coordination of a body´s limbs as if the technical interface is a body´s sensorium prolonged into the game. back

5 McGonigal, Jane: This Might Be A Game. Ubiquitous Play and Performance at the Turn of the Twenty-First Century. Dissertation. Performance Studies, University of California. Berkeley 2006, chapter 2.1, p.46-55. URL: http://avantgame.com/ McGonigal _THIS_MIGHT_BE_A_GAME _sm.pdf (1/19/2008). On the history and the use of the terms "pervasive computing" und "ubiquitous computing": Nieuwdorp, Eva: The Pervasive Discourse. An Analysis, chapter 2.1-2.3. In: ACM Computing in Entertainaent. Vol.5/Nr.2. Article 13. August 2007. URL: http://portal.acm.org/ ft_gateway.cfm?id =1279553&type= pdf&coll=GUDE&dl=ACM&CFID =15151515 &CFTOKEN=6184618 (1/12/2008). zurück

6 On "alternate reality games": Alexander, Bryan/Barlow, Nova/Dena, Christy/Phillips, Andrea/Thompson, Brooke: 2006 Alternate Reality Games White Paper. The IGDA (International Game Developers Association) Alternate Reality Games SIG. URL: http://igda.org/ arg/ resources/ IGDA-AlternateRealityGames-Whitepaper-2006.pdf (1/20/2008); Christie, Dena: Creating Alternate Realities. In: Borries, Friedrich von/Walz, Steffen P./Böttger, Matthias (ed.): Space, Time, Play, see annotation 4, p.238-241; McGonigal, Jane: This Might Be A Game, see annotation 5, p.262-372; Montola, Markus/Nieuwdorp, Eva/Waern, Annika: Domain of Pervasive Gaming, p.15 ("massive puzzle games"). In: IPerG (Integrated Project on Pervasive Gaming). Kista/Nottingham/Oslo/Sankt Augustin/Tampere/Visby a.o. 2006. Deliverable D5.3B. URL: http://iperg.sics.se/ Deliverables/ D5.3b-Domain-of-Pervasive-Gaming.pdf (1/12/2008); Szulborski, Dave: This Is Not A Game. A Guide to Alternate Reality Gaming. Macungie/Pennsylvania 2005.

Examples:

Electronic Arts: Majestic, 2001. In: Alexander, Bryan/Barlow, Nova/Dena, Christy/Phillips, Andrea/Thompson, Brooke: 2006 Alternate Reality Games White Paper, see above, p.52s.; Squire, Kurt: Majestic. Blurring the Lines between Computer Games and Reality. In: Borries, Friedrich von/Walz, Steffen P./Böttger, Matthias (ed.): Space, Time, Play, see annotation 4, p.212s.

DreamWorks: The Beast/The A.I. Games, 2001. URL: http://www.cloudmakers.org (1/19/2008); http://www.seanstewart.org/ beast/ intro (1/19/2008). In: McGonigal, Jane: This is Not a Game. Immersive Aesthetics and Collective Play. In: Digital Arts & Culture 2003 Conference Proceedings, Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology. Melbourne 2003. URL: http://www.seansteward.org/ beast/ mcgonigal/ notagame/ paper.pdf (7/31/2007); McGonigal, Jane: This Might Be A Game, see annotation 5, p.264-300,310-367; Montola, Markus/Nieuwdorp, Eva/Waern, Annika: Domain of Pervasive Gaming, see above, p.22; Salen, Katie/Zimmerman, Eric: Rules of Play, see annotation 4, p.575-578; Szulborski, Dave: The Beast. An Alternative Reality Game Defines the Future. In: Borries, Friedrich von/Walz, Steffen P./Böttger, Matthias (ed.): Space, Time, Play, see annotation 4, p. 228s. back

7 Compare authors classifying "alternate reality games" as "sub-genre" of "pervasive games": Montola, Markus: Exploring the Edge of the Magic Circle. Defining Pervasive Games, chapter 3.2. In: DAC (Digital Arts and Culture) 2005 Conference. IT University of Copenhagen 2005. URL: http://users.tkk.fi/ ~mmontola/ exploringtheedge.pdf (1/19/2008); Montola, Markus/Nieuwdorp, Eva/Waern, Annika: Domain of Pervasive Gaming, see annotation 6, p.11,15. back

8 On "pervasive games" as generic term: Montola, Markus: Exploring the Edge of the Magic Circle, see annotation 7, chapter 3; Nieuwdorp, Eva: The Pervasive Interface. Tracing the Magic Circle. In: Proceedings of DiGRA (Digital Games Research Association) 2005 Conference: Changing Views – Worlds in Play. URL: http://intranet.tii.se/ components/ results/ files/ nieuwdorpfinal.doc (1/12/2008); Walther, Bo Kampmann: Atomic Actions – Molecular Experience. Theory of Pervasive Games, p.113. In: Proceedings of PerGames 2005. Second International Workshop on Gaming Applications in Pervasive Computing Environments. München 2005. URL: http://www.ipsi.fraunhofer.de/ ambiente/ pergames2005/ papers_2005/ PROCEEDINGS_PerGames_2005.pdf (12/3/2005); Walther, Bo Kampmann: Pervasive Gaming: Formats, Rules and Space, chapter Pervasive Gaming Formats. In: Fibreculture. Issue 8 – Gaming Networks. October 2006. URL: http://journal.fibreculture.org/ issue8/ issue8_walther.html (11/26/2007).

Against the use of the term "pervasive games" as generic term: Brown, Dakota Reese: Pervasive Games Are Not A Genre! (They are a sub-genre.) A theoretical model for the genre of appropriative games and a technical approach to a single-player appropriative gaming experience, p.4s.,8ss. Master of Science in Digital Media. School of Literature, Communication & Culture. Georgia Institute of Technology. Atlanta/Georgia 2007. URL: http://www.avantgaming.com/ papers/ dakota_brown_appropriative_games.pdf (10/29/2007). back

9 Salen, Katie/Zimmerman, Eric: Rules of Play, see annotation 4, p.95; Salen, Katie/Zimmerman, Eric: This is not a Game. Play in Cultural Environments, p.15. In: Level Up Conference Proceedings. Universiteit Utrecht 2003. URL: http://www.digra.org/ dl/ db/ 05163.47569 (12/16/2007); Salen, Katie/Zimmerman, Eric: Game Design and Meaningful Play. In: Raessens, Joost/Goldstein, Jeffrey (ed.): Handbook of Computer Game Studies. Cambridge/Massachusetts 2005, p.76.

"Magic circle" is the English translation of the term "toovercirkel" in the netherlandisch original text: Huizinga, Johan: Homo Ludens. Proeve eener bepaling van het spel-element der cultuur. Haarlem 1938, chapter I Aard en betekenis van het spel als cultuurverschijnsel, p.15,30. Compare p.17: "tooverkring van het spel." (New in: Huizinga, Johan: Verzamelde werken V (Cultuurgeschiedenis III). Homo Ludens...Haarlem 1950, p.37,39,48. URL: http://www.dbnl.org/ tekst/ huiz003homo01_01/ huiz003homo01_01_0002.htm (3/27/2008)) The English translation uses for three cases (for "toovercirkel" and "tooverkring" on p.15,17 and 30 in the netherlandish original of 1938) the term "magic circle" (Huizinga, Johan: Homo Ludens. A Study of the Play Element in Culture. Boston 1955, chapter "Nature and Significance as a Cultural Phenomenon". New in: Salen, Katie/Zimmerman, Eric (ed.): The Game Design Reader. A Rules of Play Anthology. Cambridge/Massachusetts 2006, p.105s.,113), meanwhile the German translation of Hans Nachod (Huizinga, Johan: Homo Ludens. Vom Ursprung der Kultur im Spiel. Amsterdam 1939/Hamburg 1956) uses three different terms: "Zauberkreis" (p.17), "Zauberkreis des Spiels" (p.19) and "Zauberzirkel" (p.27).

Huizinga uses the term "toovercirkel" in two meanings:

- local-related as a circle respectively playground for performances of the 'magic' (original, p.15,30; English translation p.104s.,113);

- perception-related as circle respectively play with magic impact (original, p.16; English translation, p.105).

The person-related meaning of the term "toovercirkel" as a circle of persons performing magic respectively as a group of magicians is not used by Huizinga (not also in further mentions of "toovercirkel" in chapters IV and XII, edition Haarlem 1950, p.106,245. URL: http://www.dbnl.org/ tekst/ huiz003homo01_01/ huiz003homo01_01_0005.htm (3/27/2008), http://www.dbnl.org/ tekst/ huiz003homo01_01/ huiz003homo01_01_0013.htm (3/27/2008)). He concentrates his analyses on the magic impact and magicians marking fields as playgrounds for magic acts ("zijn gewijde ruimte", original, first edition of 1938, p.30). The most relevant sentence for all problems of transfers of the term "toovercirkel" to pervasive games is:

"De orde, die het spel oplegt, is absoluut. De geringste afwijking daarvan bederft het spel, ontneemt het zijn karakter en maakt het waardeloos." (original, p.15)

"Play demands order absolute and supreme. The least deviation from it 'spoils the game', robs it of its character and makes it worthless." (English translation, p.105)

On the relevance of Huizinga´s "Homo Ludens" for computer games:

Brinkerink, Maarten: De magie van het spel. Participatie, identiteit en esthetiek als fondamentele onderdelen van de spelbeleving. Master course paper. Instituut Medie en Re/presentatie. Faculteit der Letteren. Universiteit Utrecht 2005. URL: http://maartenbrinkerink.net/ wp-content/ portfolio/ papers/ de_magie_van_het_spel.pdf (1/2/2008); Rodriguez, Hector: The Playful and the Serious. An Appropriation to Huizinga´s Homo Ludens. In: Gamestudies. Vol.6/Issue 1. December 2006. URL: http://gamestudies.org/ 0601/ articles/ rodriges (11/10/2007). back

10 Salen, Katie/Zimmerman, Eric: Rules of Play, see annotation 4, p.370-373,449s.,458,577; Salen, Katie/Zimmerman, Eric: This is not a Game, see annotation 9, p.20,22 refering to: Bateson, Gregory: A Theory of Play and Fantasy. A Report on Theoretical Aspects of the Project for Study of the Role of Paradoxes of Abstraction in Communication. In: Approaches to the Study of Human Personality. American Psychiatric Association. Psychiatric Research Reports. No. 2/1955, p.39-51 (New in: Salen, Katie/Zimmerman, Eric (ed.): The Game Design Reader, see annotation 9, p.314-328). back

11 Bateson, Gregory: A Theory of Play and Fantasy, see annotation 10, sections 5, 13, 15, 17 and 19s. back

12 Salen, Katie/Zimmerman, Eric: Rules of Play, see annotation 4, p.98 (Salen, Katie/Zimmerman, Eric: This is not a Game; see annotation 9, p.16): "The magic circle can define a powerful space...But it is also remarkably fragile as well, requiring constant maintenance to keep it intact." back

13 Salen, Katie/Zimmerman, Eric: Rules of Play, see annotation 4, p.585 (Salen, Katie/Zimmerman, Eric: This is not a Game; see annotation 9, p.28). Compare p.587: "Considered as a cultural environment, a game plays with the possible erasure of the magic circle and therefore plays with the possibility of its own existence. However, some semblance of the magic circle always remains." back

14 Montola, Markus: Exploring the Edge of the Magic Circle, see annotation 7, chapters 2-4. back

15 Montola, Markus: Exploring the Edge of the Magic Circle, see annotation 7, chapter 1. back

16 McGonigal, Jane: This Might Be A Game, see annotation 5, chapter 2.3, p.66. Compare p.509 noting that "the disrupted magic circle...has been theorized extensively in pre-digital play." back

17 Brown, Dakota Reese: Pervasive Games Are Not A Genre, see annotation 8, p.49s. back

18 Furthermore: Harvey, Alison: The Liminal Magic Circle: Boundaries, Frames, and Participation in Pervasive Mobile Games. In: Journal of the Mobile Digital Commons Network. Vol.1/Issue 1, 2006. URL: http://wi.hexagram.ca/ 1_1_html/ 1_1_harvey.html (2/12/2008). back

19 Nieuwdorp, Eva: The Pervasive Interface, see annotation 8, p.4. back

20 The interface model presented below is not restricted to pervasive games establishing autonomous game worlds as or with virtual worlds (see chapter "Examples 2" and "3"). back

21 Nieuwdorp, Eva: The Pervasive Interface, see annotation 8, p.6,8ss. back

22 Nieuwdorp, Eva: The Pervasive Interface, see annotation 8, p.6s. back