IASLonline NetArt: Theorie

Thomas Dreher

History of Computer Art

VI. Net Art: Networks, Participation, Hypertext

VI.1 Computer Networks

- VI.1.1 From Timesharing to the Internet

- VI.1.2 Participation in Networks of the Eighties

- Illustrations Part IX: Net Art: PPT / PDF

- Table of Contents

- Bibliography

- Previous Chapter

- Next Chapter

In the sixties and seventies American scientists asked if computers can´t be used for other purposes than for calculation tasks. The quest for alternative functions led to efforts to develop adequate interfaces for terminals serving as accesses to central mainframe computers and as a means to communicate with participants on other terminals (see chap. VI.2.1).

After the development of solutions for "multi-tasking" by dividing a processor´s capacities the computer researchers worked out "multi-access". It offers accesses from several terminals or "operators" to a central computer:

...during the normal running of the machine several operators are using the machine during the same time. To each of these operators the machine appears to behave as a separate machine. 1

Between 1957 and 1959 the concept for timesharing was developed to ameliorate the use of the computing power. Timesharing made possible a better utilisation of computer capacities being accessible from various terminals. Since 1964 the first workable timesharing systems were realised. 2 These systems subdivided the computing time of a computer in sections lasting milliseconds and distributed these sections to the programmes started by the participants on the terminals. The time needed by a computer to response via timesharing to requests by terminals rested within the "timespan of seconds". 3

In the sixties Joseph Carl Robnett Licklider and Douglas Carl Engelbart conceptualise the interface between humans and computers as a cooperation of several participants using the same "intelligence augmenting tool" 4 for operations with "symbols" 5: to store character strings, to retrieve documents from the memory, to process these data and to store the processed data. 6 A keyboard and an electronic pen or a mouse are the means to process characters presented on a monitor. With these means functions can be easily activated. 7 Computers formerly used as calculators can be used with these forerunners of menus´ icons dominantly to process text and graphics.

Wilson, Roland B.: Cartoons for Joseph Carl Robnet Licklider´s and Robert W. Taylor´s "The Computer as Communication Device", 1968 (Licklider/Taylor: Computer 1968/1990, p.26).

During the sixties and the seventies the development of the human-computer interface and the development of computer networks are joined: The terminals connected with mainframe computers via timesharing are replaced by computers connected to networks via high performance cables. The interfaces of these computers (keyboard, mouse, desktop, see chap. VI.2.1, VII.2) anticipate the interfaces being usual by the personal computers since the eighties.

Since the end of June 1970 the XEROX Palo Alto Research Center is formed as a private research organisation. There William K. English, Alan C. Kay, Robert M. Metcalfe, George E. Pake, Robert W. Taylor, Larry Tesler, John Warnock and others develop networks between microcomputers, the Alto (1972/73) as a precursor of the eighties personal computers. 8 After the local area networks with terminals connected to mainframe computers 9 the ARPANET was first installed in 1969 as a new development of networks. It connected the computers of American universities working on military projects via cable systems (Ethernet) using dedicated lines faster than telephone cables. 10 In the eighties further networks were installed for specific research projects like MILNET (Military Network, since 1983), BITNET (Because It's Time NETwork), WSFNET (National Science Foundation Network) and CSNET (Computer Science Network). 11

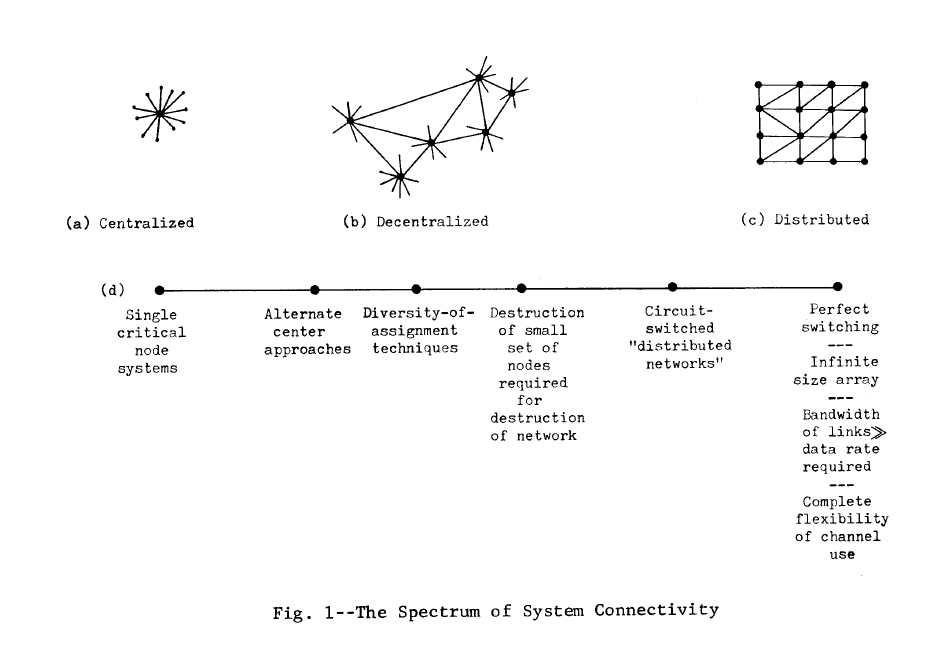

A technical precondition of the internet developed Paul Baran with his concept for "packet switching" dividing digitised elements in packets and adding informations being necessary for the recombinations after the posting of the packets via varying connections (cables and hosts) to the target computer. "Nodes" (hosts) receive the packets and send them to the next well-functioning "node" ("rapid store-and-forward design"). Non-functional "nodes" are circumvented. With this concept Baran formed in 1964 the basis for decentral networking. 12 Between 1968 and 1970 the members of the Internet Message Processing (IMP) Group Will Crowther and Dave Walden solved the routing problems of the "packet switching" for the ARPANET with only 150 instructions in machine language. This was only one tenth of the number of commands determined as acceptable in the definition of the framework conditions for the ARPANET´s development. 13

Baran, Paul: The Spectrum of System Connectivity, 1964

(Baran: Communications V 1964, p.6, fig.1).

Protocols code and decode the data packets. In 1970/71 the transfer of data from one computer to another was made possible by the file transfer protocol (FTP). 14 In the ARPANET the TCP/IP protocol (Transmission Control Protocol/Internet Protocol) coordinated the transfer of data packets between networks. This protocol constituted the fundament of the later developed internet and its protocol layers. 15

Beside the high capacity cables of the ARPANET networks were built in the eighties connecting personal computers via telecommunication in using modems with acoustic coupler on which the telephones´ handsets had to be placed. The dial-in procedures with the program MODEM to bulletin board systems, newsgroups and MUD´s 16 were complicated. Before the Mosaic Browser (since 1993) was developed for the World Wide Web 17 participants operated in the internet in using commands that had to be learned. 18 Since 1980 the timesharing services being offered on universities´ computers were used to built the first nodes between the networks. These nodes constituted the fundament for the server structure of the internet being extended in the nineties. 19

During the eighties and the early nineties the participants of Bulletin Board Systems (BBS) developed an awareness of "virtual communities" 20 communicating with each other in writing from remote places without time delay. The free and open software of networks constantly developed further as well as the abolished division between readers and authors (see chap. VI.1.2) are cornerstones of the demand for a free, unrestricted data exchange initiating the start of net activism. In the nineties activists rejected efforts to restrict web accesses through censorship, copyright, charges and other barriers. 21

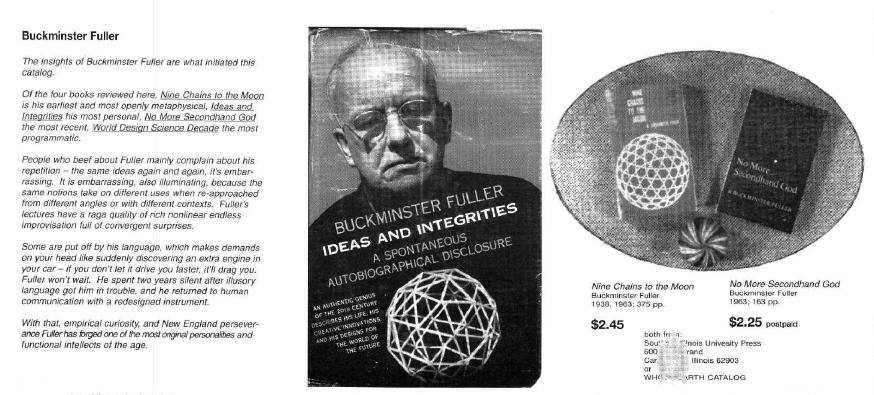

In 1985 the network The WELL (the Whole Earth ´Lectronic Link) started in Sausalito/California. Its system was based on a BBS programme for video conferences (PicoSpan für Unix) offering all participants access to a database. 22 The WELL was an online proceeding of the information exchange constituting the core of the "Whole Earth Catalog". After its first print in autumn 1968 Stuart Brand edited updates until 1994. This `catalogue in progress´ featured books and technologies inspiring people living in the Bay Area´ s surroundings of the commune keepers and the grassroots activism. Buckminster Fuller´s all-encompassing world view was the main inspiration:

The insights of Buckminster Fuller are what initiated this catalog. 23

Brand, Stewart (ed.): Whole

Earth Catalog. Fall

1968: Buckminster Fuller

(Brand: Earth 1968, p.3).

The transformation of the print version into The WELL included fora being open for the readers´ propositions and contributions. The "network forum" for the communication between the authors of the print versions was developed further into public conferences and newsgroups. 24

Following Fred Turner the counterculture of the sixties ´ New Communalist movement with estimated between two and six thousand communes in the U.S.A., many of them located in the Bay Area, was converted in the eighties in "virtual communities" by The WELL. 25

One of the public conferences on The WELL was the Art Com Electronic Network (ACEN, see chap. VI.1.2). 26

The I.P. Sharp Associates Network (IPSANET) offered clients accesses to its mainframe computers. With acquirable network-specific terminals clients were able to reach nodes being connected with transocean cabels and a "packet switching" transmission technique. 27 In April 1979 I.P. Sharp Associates Network put capacities at the disposal of artists communicating with each other for two hours in a Computer Communications Conference from terminals in 19 towns of America, Australia, Japan, Canada and Austria. 28 Since 1980 artists could employ a mailbox system developed by Gottfried Bach for ASCII e-mails in the I.P. Sharp Associates Network. In 1982 this "Artbox" developed further to ARTEX (Artists´ Electronic Exchange Program). Until 1990 30 artists used ARTEX in projects with participants operating on terminals located in several places. 29

Nodes of the I.P. Sharp Associates Network.

User manual for ARTEX in the I.P. Sharp Associates Network, November 1982.

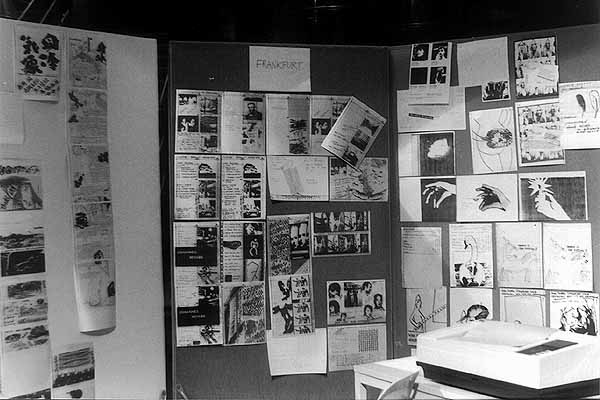

"14 artists or groups" living in 15 cities (Amsterdam, Athen, Bath, Florenz, Frankfurt, Honolulu, Istanbul, Pittsburgh, San Francisco, Sydney, Tokyo, Toronto, Vancouver, Wellfleet, Vienna) participated in the project "The World in 24 Hours". In 1982, during the Ars Electronica Festival in Linz, Robert Adrian X administrated the telephone connections to the I.P. Sharp Associates Network. At 12.00 a.m. local time people in the participating cities could get in contact with the organisation centre in Linz. In their changes from place to place during 24 hours the participants followed the midday sun around the globe. Participants in Linz had three telephone lines to interchange faxes and videos with varying participants. For a telephone long distance transmission a Slow Scan TV Transceiver transformed videos into audio signals. They had to be retransformed into video signals on the receiver side. I.P. Sharp Associates Network provided "Artbos and Confer programs" as well as opportunities to transmit computer graphics. Via the Confer program the participants in 15 cities were connected to the organisation centre in Linz. Many participants used the "Computer Timesharing (I.P. Sharp APL/Network)" as well as telefax and slow scan television. In Linz the resulting output was presented on partition walls installed in the foyer of the ORF-Landesstudio Oberösterreich. "Connectivity" 30 was the main feature of "The World in 24 Hours". 31

Adrian X, Robert: The World in 24 Hours. Österreichischer Rundfunk (ORF), Landesstudio Oberösterreich, Linz 1982: posting up of telefacsimiles from Tokyo, Frankfurt and Wien.

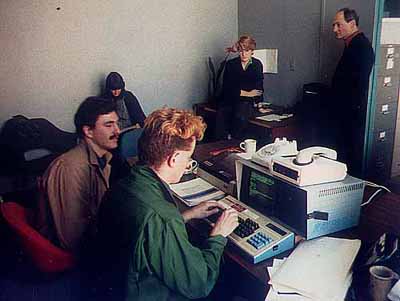

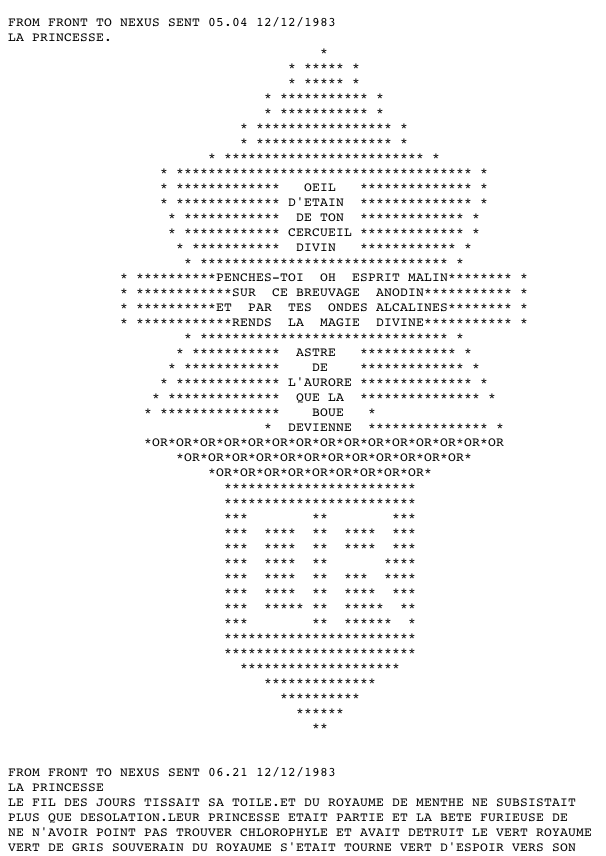

In 1983 Roy Ascott organised a collaborative writing project: Participants in Bristol, Honolulu, Paris, Pittsburg, Sidney, Vancouver and Vienna cooperated in writing text contributions for the roles of a "planetary fairytale". On projections in the Musée d´Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris visitors of the exhibition "Elektra" could follow the writers developing «La Plissure du Texte» in the e-mail network ARTEX. 32

Ascott, Roy: La Plissure du Texte, 1983. Tom Klinkowstein and Greg McKenna at a terminal for the I.P. Sharp Associates Network in La Mamelle, San Francisco.

Ascott, Roy: La Plissure du Texte, 1983. Text contribution (detail) from Vancouver for La Princesse.

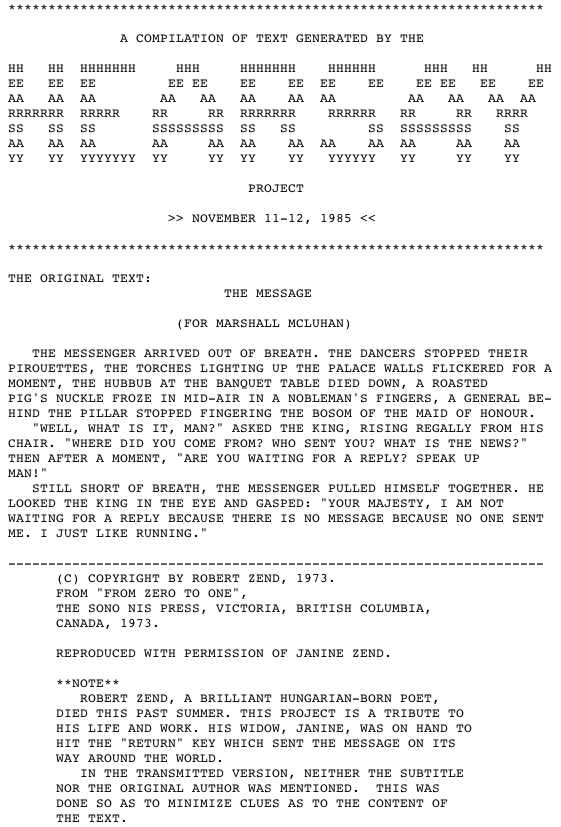

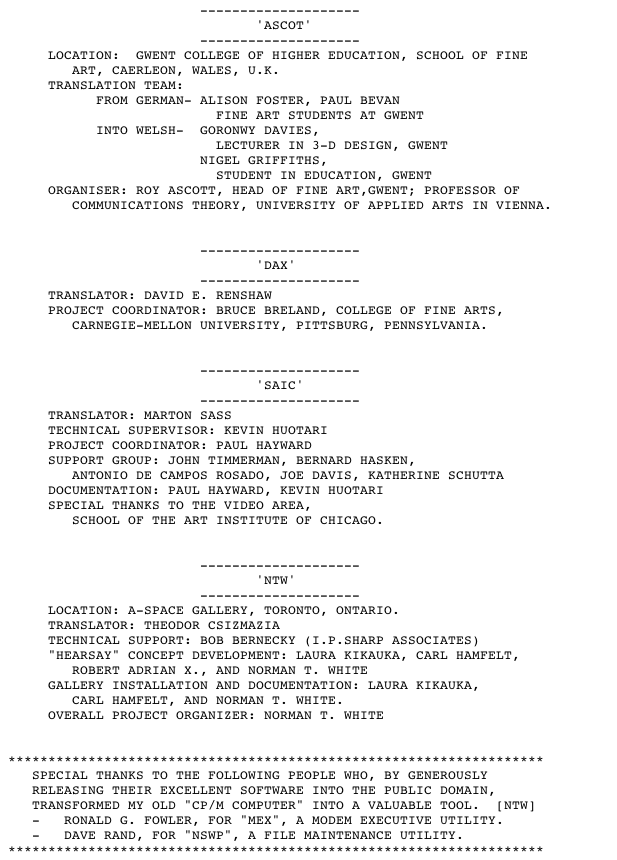

In 1985 Norman White initiates a translation chain in "Hearsay": Within 24 hours Robert Zend´s "The Message (For Marshall McLuhan) " (published in Zend´s "From Zero to One", 1973) was sent on I.P. Sharp Associates Network from one participating centre to the next and translated. The eight participants in eight centres in England, America, Canada and Japan modified the text from one translation to the next. For comparisons the following quotes offer the English versions from the start and the end of the chain: "...a General behind the pillar stopped fingering the bosom of the maid of honour" is changed into "The king sat calmly on his festive chair, his hand on a woman´s breast." 33

White, Norman: Hearsay, 1985. Left: the start of the

web documentation.

Right: the end.

Within the I.P. Sharp Associates Network the costs of a connection did not change with different distances of recipients. With Bulletin Board Systems like The WELL (see chap. VI.1.1) "it was almost impossible to link networks across the oceans due to the slow modem speeds and high phone costs... 34

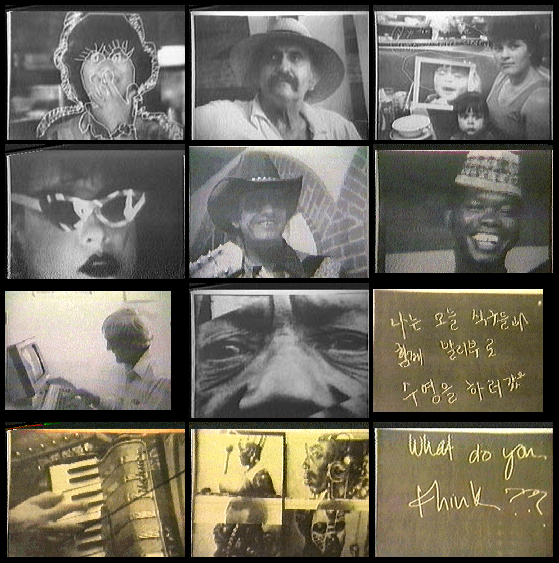

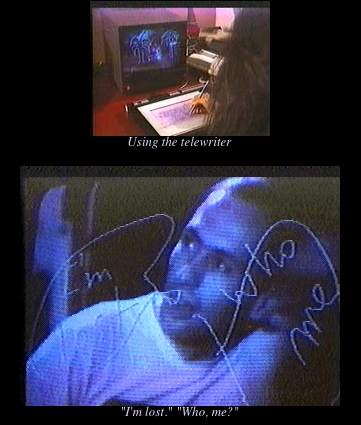

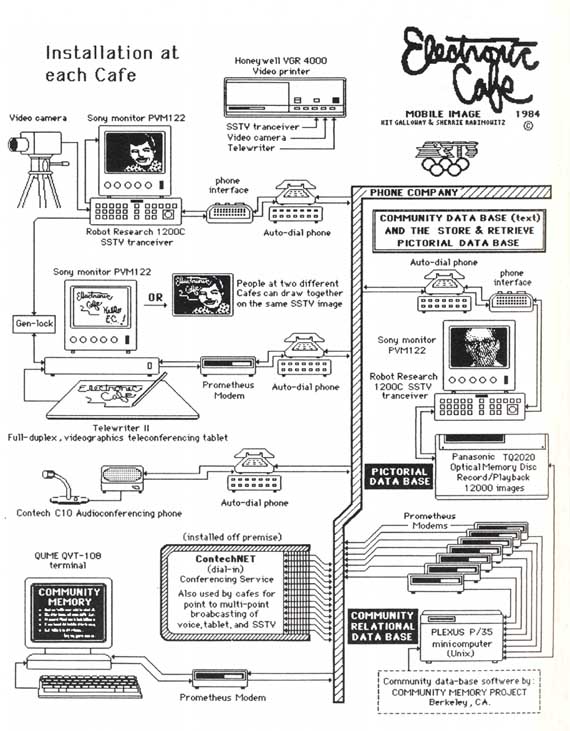

In the projects for the I.P. Sharp Associates Network mentioned above the participation was limited to invited guests working within the context of art. These projects presented the participants´ contributions successively. But this is not a use of the connectivity as a precondition for a participation in favor of the interactions´ social aspects – in contrast to Kit Galloway´s and Sherrie Rabinovitz´s Los Angeles based project "Electronic Cafe". In 1984 the café of the Museum of Contemporary Art and four cafés in districts with publics of different ethnic groups offered to their visitors terminals with connections to the bulletin board of the Community Memory in Berkeley. The navigation in the Bulletin Board was designed as simple as possible. The Bulletin Board System included a database with texts and photos created by participants. A telewriter could be used by participants as a pen to make up handwritten documents – texts and drawings – and to post them. Video prints could be transfered via a Slow Scan Video System (SSTV). Participants on terminals of two different cafés could draw simultaneously on an image, store it in the database for images and publish it. 35 For the first time a Laser Optical Disk Recorder was used as a database for images in a network. 36

Galloway, Kit/Rabinovitz, Sherrie: Electronic Café, Los Angeles 1984.

Diagram of the installation´s functions as they were installed in

each café (Youngblood: Raum 1986, p.298).

The project can be understood as a "prototype of all internet cafés" as well as of the "context-based systems" 37, the platforms of the nineties´ internet refering to urban contexts. Gene Youngblood writes on the "Electronic Café":

...the information environment as commons, equally accessible to everyone. 38

Youngblood features the inclusion of image documents into the network, the openness of the Bulletin Board unedited for contributions of all kinds and the possibility to send contributions anonymously as characteristics of the "Electronic Café":

Democracy is threatened if we can´t participate anonymously in communities defined by telecommunication, not geography. 39

With the usability of terminals for participants of different income groups and the urban context of Los Angeles as a social reference framework the "Electronic Café" anticipates in 1984 "context-based systems" of the nineties like "De Digitale Stad" in Amsterdam (since 1993) and the "Internationale Stadt" in Berlin (1994-98) 40 using the availability of personal computers and telecommunication networks in efforts to build a new community. The social and libertarian aspirations of the sixties and seventies were combined in the eighties and nineties with the widely distributed personal computers 41 in ways offering virtual and urban communities to complement each other.

Galloway, Kit/Rabinovitz, Sherrie: Electronic Café, Los Angeles 1984.

Links: Videoprints. Rechts: Telewriter.

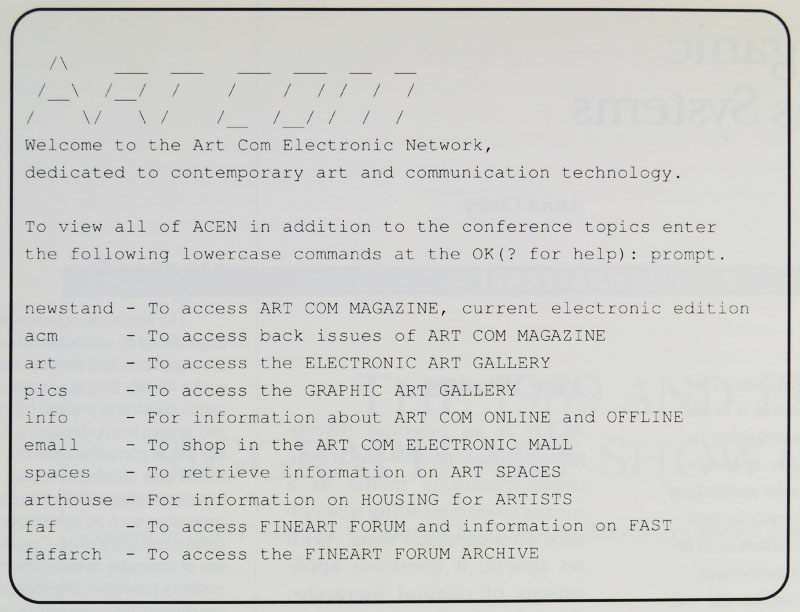

In spring 1986 the artists´ group Art Com opened a "public conference" on the Bulletin Board System The WELL (see chap. VI.1.1). In 1986 Carl Eugene Loeffler, Lorna and Fred Truck, Anna Couey and others installed the Art Com Magazine on The WELL and as a newsgroup on USENET informing their readers on current developments of the art, computer technology and networks. The readers are invited to post comments and to engage themselves as editors:

Art Com Magazine attempts to realize publishing as a creative (art publishing as art work) and communicative medium shaped by the community that reads it. 42

Anna Couey´s invitation to participate takes up the openness for cooperation being usual in The WELL: In Bulletin Board Systems a reader reacts to existing contributions with his own comments and with them he offers impulses to other readers for a continuation of the dialogue. Couey´s conception of the art work as a "communication system" takes up the sixties and seventies developments of an engaged art and anticipates the later collaborative writing projects. George Landow and others address the later emerging change of a person´s roles between reader and author and designate it as "wreader" (writer/reader). With it they mark the changeover from a participative action art to direct social interactions between remote participants. 43

Art Com Electronic Network: Start Menu, since 1990

(Couey: Art Works 1991, p.128, fig.1).

In 1989 Anna Couey, Carl Eugene Loeffler and Fred Truck installed the Art Com Electronic Mail for the distribution of books, videos and software by and on artists. On the one hand the Whole Earth Catalog was extended in the Art Com Electronic Mail by product descriptions for the section media art. On the other hand a precursor of contemporary webshops was installed with a "checkout cashier".

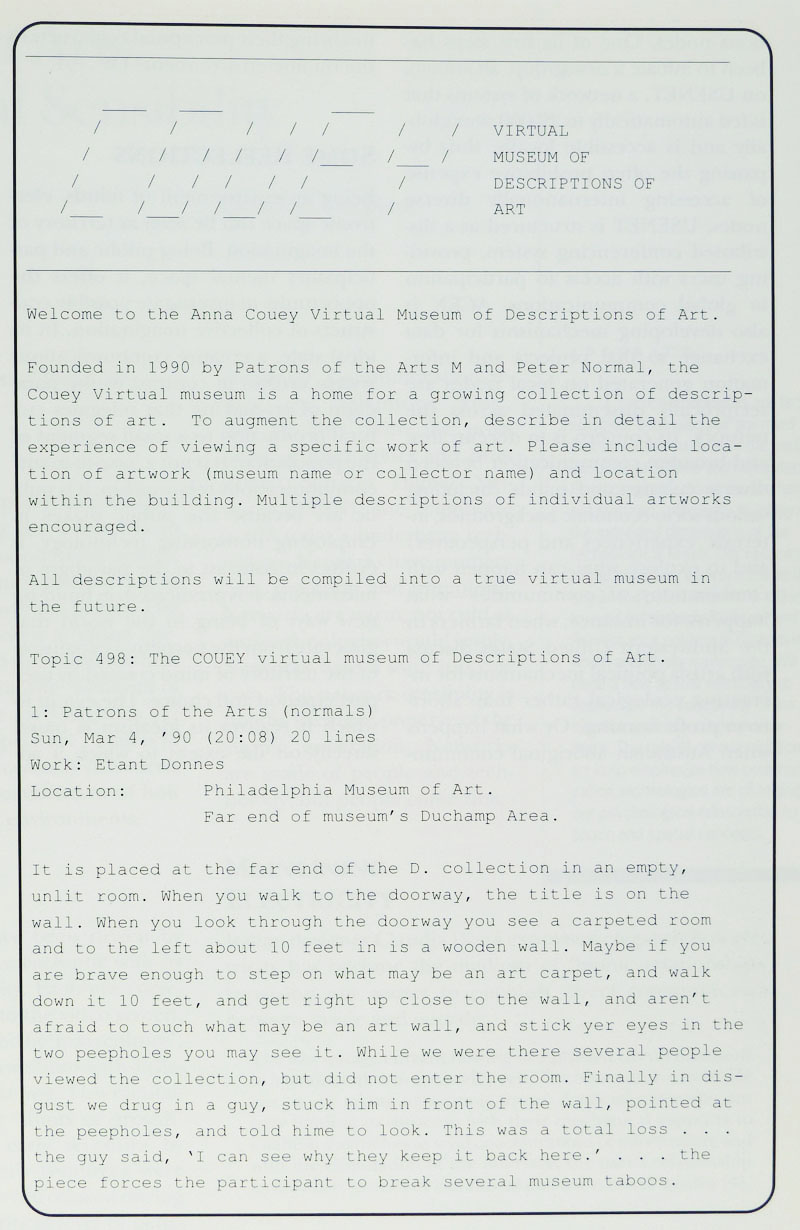

The Normals: Couey Virtual Museum of Descriptions of Art, Art Com Electronic Network, since 1990 (Couey: Art Works 1991, p.129, fig.2).

In 1990 a Bulletin Board was started and organised as a Virtual Museum containing descriptions of art works written by the authors´ group "the Normals" (with Anna Couey). The "Couey Virtual Museum of Descriptions of Art" could be extended by new contributions from "wreaders". The Virtual Museum was open for descriptions of concepts for works either waiting to be realised or being notations independent from realisations:

Users variously describe their experience of seeing a work of art, or create their own through description. 44

Some collaborative projects by ACEN anticipating future forms to use the internet for literature were "The Heart of the Machine" of Dromos Editions (Ian Ferrier and Fortner Andersen, since 1987), "Das Casino" by Carl Eugene Loeffler and Fred Truck (1987-88) as well as "Exquisite Corpse" by Gil Mina Mora (since 1988). "In the Heart of the Machine" was a novel in instalments. In preparing the next chapters the authors incorporated biographies sent by participants. "Das Casino" was a "bulletin board topic" with participants writing a dialogue in a "conceptual game of roulette". The topic included the fictive money Casinobux and a program generating random numbers. An alternative to this "participatory text performance" offered Mora´s "Exquisite Corpse" in transforming the surrealist strategy of a collaborative successive creation of drawings («cadavre exquis») into a text-producing strategy: Participants could not read more than the last line of the newest contribution. The 69th contribution was chosen as the end of the text. 45

In the internet the cyberspace frequently invoked in the eighties was not an illusionary space for the observers´ immersion but a space for dialogues and discussions. The internet was described by initiators of ARTEX projects like Robert Adrian X and Roy Ascott as an information room with worldwide accesses. 46 ARTEX participants could use the oversea cables of the I.P. Sharp Associates Network meanwhile the participants of The WELL constituted locally limited communities like ACEN on the West Coast of the U.S.A. by the reasons mentioned above. Their members could meet each other if the result of written dialogues was the fixation of a date for a direct communication on the complicated navigation in the internet. 47

The "Electronic Café" was constituted by the telecommunications between population groups living apart from each other in the urban context. The telecommunication can be used in a local context to undermine social and racial barriers being kept alive in urban spaces. Contrary to such locally based works the projects of Ascott and ACEN integrate remote participants in experiments transgressing established literary forms.

In the seventies the journal "Radical Software" offered a forum to video artists to exchange informations about new video techniques and various kinds to use them. The articles published in "Radical Software" could point out the juxtaposition of two cultures – social-critically engaged on one side and experimental formal on the other side – but not mediate between them (see chap. IV.1.1). In networks these both sides are connected tighter to each other because in public conferences a distributed authorship is practiced deconstructing hierarchies between authors and recipients. The experiment is the practice of distributed authorship: Social engagement and intelligent uses of media are no longer artistic strategies complementing each other in no other way than by "Radical Software´s" contextualisation within an alternative culture encompassing both sides unconnected. The one-way communication of cinema and television got its first alternative in the seventies´ Community TV via cable or radio. 48 In the eighties a second alternative is added by a two-way communication in fora being part of projects like the boards and topics of ACEN. In web projects since the nineties video engagement and discussion fora complement each other. In this third alternative media experiments and social criticism are no longer opposites (see chap. VI.3.4). 49

Dr. Thomas Dreher

Schwanthalerstr. 158

D-80339 München.

Homepage with numerous articles

on art history since the sixties, a. o. on Concept Art and Intermedia

Art.

Copyright © (as defined in Creative

Commons Attribution-NoDerivs-NonCommercial 1.0) by the author, June

and August 2012, December 2013 (German version)/January 2014 (English

version).

This work may be copied in noncommercial contexts if proper credit is

given to the author and IASL online.

For other permission, please contact IASL

online.

Do you want to send us your opinion or a tip? Then send us an e-mail.

Annotations

1 Strachey: Time Sharing 1960, p.340. Cf. Bunz: Geschichte 2009, p.39s.; Friedewald: Computer 2009, p.128-137. back

2 An example for an early Time Sharing system: "The Sumerian Game" by BOCES and IBM, in 1965/66 tested by students (see chap. VII.1.3.2). back

3 Friedewald: Computer 2009, p.129. back

4 "Intelligence augmenting tool" ("intelligenzverstärkendes Werkzeug"): Friedewald: Computer 2009, p. 122,130s. Cf. Bardini: Bootstrapping 2000, p.1,10ss.,19ss.,23s.,28-32,36s.; Engelbart: Intellect 1962, p.72s; Licklider/Taylor: Computer 1968/1990, p.26s. back

5 Bardini: Bootstrapping 2000, p.13; Engelbart: Intellect 1962, p.22s. back

6 Engelbart/English: Research 1968; Licklider/Taylor:

Computer 1968/1990; Rheingold: Community 1994, chap.3.

Licklider: Symbiosis 1960/1990, p.5: "Severe problems are posed by

the fact that these operations have to be performed upon diverse variables

and in unforeseen and continually changing sequences. If those problems

can be solved in such a way as to create a symbiotic relation between

a man and a fast information-retrieval and data-processing machine, however,

it seems evident that the cooperative interaction would greatly improve

the thinking process."

Engelbart: Intellect 1962, p.6: "In such a future working relationship

between human problem-solver and computer 'clerk', the capability of the

computer for executing mathematical processes would be used whenever it

was needed. However, the computer has many other capabilities for manipulating

and displaying information that can be of significant benefit to the human

in nonmathematical processes of planning, organizing, studying, etc. Every

person who does his thinking with symbolized concepts (whether in the

form of the English language, pictographs, formal logic, or mathematics)

should be able to benefit significantly."

Ebda, S. 37: "These new ways of working are basically available with

today's technology--we have but to free ourselves from some of our limiting

views and begin experimenting with compatible sets of structure forms

and processes for human concepts, human symbols, and machine symbols."

back

7 Engelbart: Intellect 1962, p.69s.; Licklider/Taylor: Computer 1968/1990, p.25,29s. Cf. Friedewald: Computer 2009, p.132 with ill.29, p.136s. back

8 Bardini: Bootstrapping 2000, p.149,153,158 (Alto Ethernet interface, end of 1973); Friedewald: Computer 2009, p.250,257,260-269,275-292,337s.; Matis: Wundermaschine 2002, p.269s.; Rheingold: Community 1993, chap.3. back

9 Engelbart: Intellect 1962, p.72. back

10 ARPANET: Bunz: Geschichte 2009, p.83-91; Roberts:

ARPANET 1995; Warnke: Theorien 2011, p.29-41.

ARPANET until the end of 1972: 24 sites were connected. Among them are

American universities, the Department of Defense, the National Science

Foundation, NASA and the Federal Reserve Board. Until 1977 the ARPANET

connected 111 mainframe computers. It was abandoned in 1990 (Stewart:

ARPANET 1996-2012). back

11 Matis: Wundermaschine 2002, p.309; Rheingold: Community 1993, chap.3. back

12 Baran: Communication 1964; Baran: Communications

I 1964; Bunz: Geschichte 2009, p.57-63; Rheingold: Community 1993, chap.3;

Warnke: Theorien 2011, p.20-26.

In 1968 Donald Watts Davies developed a packet switching procedure at

the British National Physical Laboratory independent from Baran. The developers

of the ARPANET knew the proposals of Baran and Davies on packet switching

(Hafner/Lyon: Wizards 1998, pdf p.41ss.; Matis: Wundermaschine 2002, p.306;

Roberts: ARPANET 1995; Warnke: Theorien 2011, p.26-29). back

13 Hafner/Lyon: Wizards 1998, pdf p.64,73; Pias: Computer

2010, p.122s.

On the technical implementation of the "packet switching" in

the ARPANET: Mutis: Wundermaschine 2002, p.306s.; Roberts: ARPANET 1995.

back

14 Rheingold: Community 1993, chap.3; Scheller/Boden/Geenen/Kampermann: Internet 1994, p.47-70. back

15 Bunz: Geschichte 2009, p.100-108; Warnke: Theorien 2011, p.43-47,76-86. back

16 Bulletin Board Systeme, since 1978: Rheingold: Community

1993, Introduction.

Newsgroups: Usenet News, ab 1980: Arns: Netzkulturen 2002, p.17s.; Rheingold:

Community 1993, chap.

4.

MUDs: Multi-User Dungeons (since 1979/80). Among others, "Adventure

Games" were played in MUDs. In these games questions were presented

and the players are asked for the right answers. Rheingold describes the

addictive character of the MUDs´ fictional worlds (Rheingold: Community

1993, chap.5). back

17 Berners-Lee: Web 1999, p.68-71,79,99; Scheller/Boden/Geenen/Kampermann: Internet 1994, p.282-293. back

18 Rheingold: Community 1993, chap.2 and 4. back

19 Rheingold: Community 1993, chap.4. back

20 Rheingold: Community 1993, Introduction; Turner: Counterculture 2006, p.159-162. back

21 Arns: Netzkulturen 2002, p.24-29; Barbrook/Cameron: Ideology 1996; Barlow: Cyberspace 1996; Stallman: Copyright 1996; Stallman: Software 2002; Lessig: Code 1999. back

22 Rheingold: Community 1993, chap.2; Turner: Counterculture 2005, p.499; Turner: Counterculture 2006, p.3,141s.,144. back

23 Brand: Earth 1968, p.3. Vgl. Turner: Counterculture 2006, p.57. back

24 Rheingold: Community 1993, chap.2 and 4; Turner: Counterculture 2005, p.496,499; Turner: Counterculture 2006, p.7,79s.,84,86,89,142,151s. back

25 Turner: Counterculture 2005, p.487,503; Turner: Counterculture 2006, p.5s.,63s.,142,146ss.,158s.,161s. back

26 Couey: Cyber Art 1991; Couey: Art Works 1991; Loeffler: Telecomputing 1989, p.129; Rheingold: Community 1993, chap.2. back

27 Moore: History 2005.

In 1991 Robert Adrian X said about the terminal: "I had a terminal

at home. I even have it at home, now it is an object for a museum collection.

It looks like a big portable typewriter. It contains only a keyboard with

a 300 baud acoustic coupler, and it printed everything on thermal paper.

People without terminal had to visit one of I.P. Sharp´s offices.

The equipment was quiet expensive at that time – circa 2000 $ for

a new unit. I bought my machine second hand for circa 600 $." (Baumgärtel:

Interview 1997) back

28 Interplay, 4/1/1979, from 8.00 to 10.00 p.m., organised by Bill Bartlett (Adrian X: Kunst 1995, p.10; Breitwieser: Re-Play 2000, p.300). back

29 Adrian X: Kunst 1995; Braun: Video 2000, p.4s.; Breitwieser: Re-Play 2000, p.300; Couey: Cyber Art 1991. back

30 Ascott/Loeffler: Connectivity 1991. back

31 Duration: from 9/27/1982, 12.00 a.m., to 9/28/1982, 12.00 a.m. ( Linz, local time). Lit.: Adrian X: Raum 1989, p.142,145; Adrian X: Welt 1982 (quotations, p.146); Braun: Adrian X 2001, p.114-119; Arns: Interaction 2004, chap. Electronic Space as "Communications Sculpture"; Braun: Video 2000, p.421s.; Breitwieser: Re-Play 2000, p.302; Daniels: Engineering 2010, p.21; Grundmann: Art 1984, p.86-99. back

32 Berry: Thematics 2001, p.66: "The result of this collaborative endeavor...is like a very extensive `corps exquis´ (played without the element of concealment) mixing languages, role playing, and rambling narratives in such a way as to make it nearly impossible for an outsider to follow." Lit.: Adrian X: Kunst 1995, p.11; Ascott/White et al.: Plissure 1983; Braun: Video 2000, p.422s.; Breitwieser: Re-Play 2000, p.304; Daniels: Engineering 2010, p.22; Grundmann: Art 1984, p.24,35s.,59-68; Heibach: Literatur 2003, p.88s.; Popper: Art 1993, p.124,134. back

33 Baumgärtel: Immaterialien 1997, chap. Freude am (ASCII-)Text; White: Hearsay 1985. back

34 Adrian X: Interview 2001, p.63. back

35 Youngblood: Raum 1986, p.298. back

36 Software: Lee Felsenstein and his former colleagues of the Community Memory Networks, Berkeley (since 1973, Slaton: Community Memory 2001). back

37 Arns: Interaction 2004, chap. Social Networking, Participation. back

38 Youngblood: Raum 1986, p.357. back

39 Youngblood: Raum 1986, p.358.

Rheingold: Community 1993, chap.2

on the opposite practice of The WELL: "Nobody is anonymous."

It was not possible to disconnect "pseudonyms" from the "real

userid". back

40 Arns: Netzkulturen 2002, p.52-55; Baumgärtel: Internet 1998, chap 2.1. back

41 Stewart Brand, founder of The WELL (see chap. VI.1.1), to Howard Rheingold: "The personal computer revolutionaries were the counterculture." (Rheingold: Community 1993, chap.2) back

42 Couey: Art Works 1991, chap. Art Com Magazine. back

43 The "wreader" is thematised by scholars as reader eliciting relations in hyperfictions. There are transitions from an active reading of hyperfictions to the participation in collaborative writing projects (Heibach: Literatur 2003, p.50 with ann.86; Landow: Hypertext 2004, chap. Animated Text; Rau: Wreader 2001; Simanowski: Tod 2004, p.87). The reader is mentally activated by multilinear links (see chap. VI.2.2). A wreader acts in virtual fora similar to authors of public letters when he tries to provoke with his own remarks other readers to react critically to his contribution. back

44 Couey: Art Works 1991. back

45 Couey: Art Works 1991 (quotations); Couey: Cyber

Art 1991; Gangadharan: Mail Art 2009, p.292ss.; Loeffler: Art Com Electronic

Network 1988, p.321; Loeffler: Telecomputing 1989.

Judy Malloy´s hyperfiction "Uncle Roger" (1986-87) is featured in chap. VI.2.2.

back

46 Adrian X: Kunst 1984, p.79 (ARTEX): "If artists´

telecomm is to have any reality it must seek to operate on a global basis...Artists

who really want to operate in the electronic space of telecommunications...must

take into account the equipment available to their partners in other parts

of the world..."

Ascott: Art 1984, p.35s. (ARTEX): "...the act is indifferent to the

geographical location of its contributors...There can be this sense of

out-of-body experience, joining up with others in the aetheric, electronic,

and totally timeless space." back

47 Rheingold: Community 1993, chap.2. back

48 Taesdale: Videofreex 1999; Dreher: Radical Software 2004, chap. video and TV. back

49 Dreher: Participation with Camera 2007, chap. TV-Programme and Participation, with ann.9 and 10; Dreher: Radical Software 2004, chap. Documentation and Intervention, Mapping & Acting. back

[ Table of Contents | Bibliography | Next Chapter ]

[ Top | Index NetArt | NetArt Theory | Home ]