IASLonline NetArt: Theory

Thomas Dreher

History of Computer Art

V. Reactive Installations and Virtual Reality

V.2 Seamless Total Simulation versus Interface Architecture

- V.2 Seamless Total Simulation versus Interface Architecture

- Illustrations Part VIII: Reactive Installations and Virtual Reality: PPT / PDF

- Table of Contents

- Bibliography

- Previous Chapter

- Next Chapter

The goal of presentations with head mounted displays and data gloves was to design the interface to virtual reality as seamless as possible. As it is usual in their daily life´s body coordination, observers move their bodies in a gravitational world meanwhile they orientate themselves visually in a gravitationless simulation. 1 Observers should be able to move in simulated worlds as if they were real, nevertheless they should be able in the virtual reality to coordinate operations transgressing the body actions under gravitational conditions.

Fleischmann, Monika/Strauss, Wolfgang: Home of the Brain, virtual reality installation, 1991/92 (Kluszczynski: Data 2011, p.70).

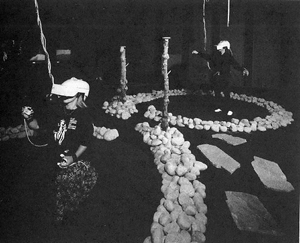

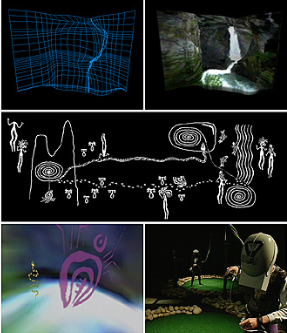

In installations like "Home of the Brain" (1991/92) by Monika Fleischmann and Wolfgang Strauss 2, "Placeholder" (1993) by Brenda Laurel and Rachel Strickland 3 and "Osmose" (1995) by Char Davies 4 observers can enter and explore the spaces of images with motions of feets, hands and eyes in using virtual reality (VR) interfaces for heads and hands. The installations for data helmets and data gloves need a limited real space enabling observers to act obstacle-free in exploring the simulated worlds. In "Placeholder" the spaces for the actions of two observers with data helmets and data gloves are enframed by stones. By tactile means observers gain knowledge of the limited gravitation-bound area for their actions in a gravitationless virtual world binding the capabilities for visual perception. 5

Laurel, Brenda/Strickland, Rachel: Placeholder, virtual reality installation, 1993.

On the opposite to these "inclusive environments" with `seamless entrances´ to simulations the "responsive environments" by Krueger, Shaw or Weibel (see chap. V.1) offer observers thechnical interfaces as `seams´ between the gravitation-bound real space and the simulated worlds. 6 The `seam´ as a technical (interface 1) and cognitive interface (interface 2, see chap. VIII.2) can be a subject of the observation models realised by artists and programmers as "responsive environments". 7

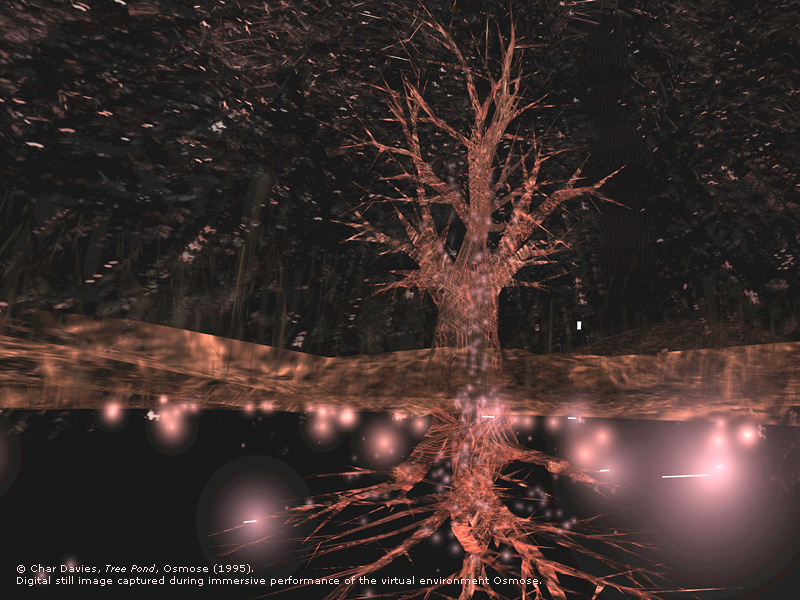

Davies, Char: Osmose, virtual reality installation, 1995.

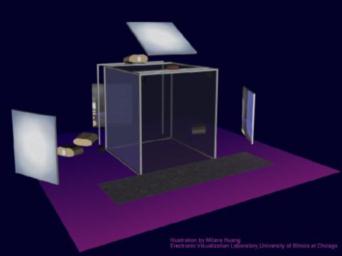

From 1991 to 1993 Daniel J. Sandin, Thomas A. DeFanti and Carolina Cruz-Neira developed "CAVE" (Cave Automatic Virtual Environment) at the Electronic Visualization Laboratory (University of Illinois, Chicago). In the 3 x 3 meter large room of this technical platform computer animations can be presented by video beamers as rear projections on three up to six walls. The animations can be abstract model worlds as well as a panorama-like simulation of a world or a state of a world (for example reconstructions of a destroyed monument´s original state). Observers wear stereo glasses (LCD shutter glasses) with sensors (between both glasses) recording their location and the head´s motions. Perspective distortions in oblique views on the projection walls are corrected:

Therefore, as the viewer moves around in the environment, the off-axis stereo projection is calculated according to his/her position with respect to the walls. 8

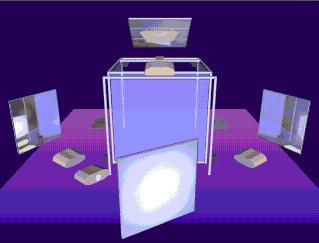

Sandin, Daniel J./DeFanti, Thomas A./Cruz-Neira, Carolina: CAVE, reactive installation, Electronic Visualization Laboratory (University of Illinois, Chicago), 1991-93.

The installations of different works programmed for the "CAVE" can require the mounting of other interface equipments for the observers´ navigations. In "ConFIGURING the CAVE" (1996) by Jeffrey Shaw, Agnes Hegedüs and John Lintermann observers are enabled to navigate in seven visual worlds by moving a puppet´s limbs. 9 Observers switch from one visual world to another by moving the hands of the puppet to its eyes.

Shaw, Jeffrey/Hegedüs, Agnes/Lintermann, John: Con FIGURING the CAVE, reactive installation in the CAVE, 1996.

The visitors are on the one hand `external observers´ exploring the programming of the virtual world and reconstructing its `internal observer´. 10 On the other hand the observers are already included in an environment trying to immerse `seamlessly´ into its simulated world. But the real space used as a facility for simulations has a limited size (10' x 10' x 9'/3,05 x 3,05 x 2,74 meter) and a projected simulation remains an inaccessible world of optical illusions. In the little cube the observers´ area for body motions is limited, and in the navigation through the projected space its illusion of depth has to be remembered for the body coordination as being part of an inaccessible `mirror world´ behind the projection walls.

Dave Pape´s "Crayoland" (1995) 11 provokes observers to turn around if they want to follow the landscape panorama being drawn with crayons and then scanned. The margins of the virtual space (200´ x 200´/60,56 x 60,56 meter) and the limits of the real space are coordinated with each other. In contrary to the "Crayoland" is in "ConFIGURING the CAVE" the depth of illusion constituting the space of the images blocked by repeated patterns of sign configurations or abstract forms: The forward driving navigation in the virtual space is replaced by an observer behavior coordinating the puppet´s limbs to explore the possible modifications of the animation´s four sides: The seeker of the depth effect (immersion) is replaced by a sliding observer.

Pape, Dave: Crayoland, reaktive Installation im CAVE, 1995.

Parallel to the navigation within the virtual world the observers use their memory for self-orientations in a narrow real space prohibiting them to walk more than some steps in one direction. But with operations on the technical interface observers can move in virtual reality as if they walk in a much wider space than in the real space of the "CAVE": Observers `walk´ in simulated worlds often meanwhile they stand still in the real space. If observers turn around to see the simulated space on walls, floor or ceiling then they act out a `standturn´ (they turn the body without walking) to move in the virtual world in circles: They move with their eyes in the virtual world in another radius than their body in the real space. A `seam´ between the real space and the projection is the precondition for a `seamless´ navigation in the virtual world(s).

No training is necessary for the coordination of motions with the tracker and one´s own body to navigate with the technical interface of the "CAVE" in virtual worlds. For observers this interface can seem to be an easy and intuitively usable entrance to the virtual world, but it is not `seemless´ like the navigation in virtual reality installations with data helmets and data gloves: The technical interface (interface 1) and the cognitive interface of the observer for his coordination of body motions (interface 2) have to be approximated to each other for cognitive intermediations (interface 3, see chap.VII.2.2, VII.2) between the real and virtual spaces with their different constituents. These intermediations for the development of adequate observing operations (action plans and schemes) can result in requirements to further exploratory actions with the feet, the head and the tracker. These characteristics allow to describe the "CAVE" as a navigable panorama with moving images (steuerbares Bewegtbild-Panorama). 12

Maurice Benayoun´s "CAVE" installation "World Skin, a Photo Safari in the Land of War" (1997) shifts the observer in the position of warzones´ tourists. Observers can´t see the spatial depth of the war zones because it is blocked by the simulation of soldiers, tanks and ruins. The technical interface includes a navigation interface for one observer and for further observers three photo cameras are hanging from the ceiling. If observers shoot with a camera on one of the war scene motifs appearing on the sides of the CAVE, then the image is erased in the area of the clicked section, leaving shadow-casting outlines of the erased people and objects. The framed section is immediately printed and can be taken away by the visitors. When the "war tourists" repeatedly shoot at the scene, the sound of camera clicking becomes a gunfire.

Benayoun, Maurice: World Skin, a Photo Safari in the Land of War, reactive installation in the CAVE, 1997.

Benayoun creates the paradox of unmoved scenes of a warzone `vivified´ by 3D animation. With it the artist developed a narrative as well as a conceptual context being especially appropriate for the technical platform CAVE. To expectations concerning an immersion provoked by the allround simulation of the CAVE Benayoun responds in thematising the expectations of warzone tourists who want to experience the horrors of the past as illustrative as possible but not too `close´. The cardboard-like presentation of war scenes prohibits heroisation and thematises expectations to simulations of historical constellations (location and events). 13

Meanwhile in installations with data helmets and data gloves obervers combine their coordination of body motions under the gravitational force `seamless´ with the simulation of weightless objects in an illusory space, the observers in a "CAVE" simulation orientate themselves at a junction (`seam´) because only a part of their motions in the narrow real space serves the navigation in the virtual space with a usually wider simulated depth.

In "responsive environments" (see chap. V.1) observers have to accomodate their body motions to technical interfaces with installation-specific designs for explorations of the programmed possibilities to navigate in the spaces of images. "Responsive environments" can not be explored without cognitive reconstructions (observing operations, interface 2) of the consequences that the navigations in the spaces of images have for the body coordination at or on the technical interface (interface 1): The `seam´ as the coordination of a technical interface with the cognitive interface (for the self orientation and the coordination of body actions) provokes the coordination of different requirements of the space of the image and the image space. The coordination of the two ways of self orientation via switches from real spaces to spaces of images and from spaces of images to real spaces (Raumbild/Bildraum, Bildraum/Raumbild) demands a processual observation of the works modificating cognitive reconceptualisations several times to integrate new experiences: The body coordination on the technical interface and the orientation in the space of the image are recoordinated in observing operations to accomodate the mental reconstruction of an installation´s functions to new experiences and to develop new explorative procedures as consequences from arising questions about the installed work. This recoordination constitutes interface 3 in mediating between interface 1 and interface 2 (see chap. VII.2.2, VIII.2).

The what and how of observations is presented in the three kinds of installations explained above (`seam´ in "responsive environments", `seamless´ in virtual reality, `seam´/`seamlessness´ in the CAVE") as an interface problem posing different requirements for observing operations mediating between the orientations in the real space and the space of the image (interface 3).

Dr. Thomas Dreher

Schwanthalerstr. 158

D-80339 München.

Homepage with numerous articles

on art history since the sixties, a. o. on Concept Art and Intermedia

Art.

Copyright © (as defined in Creative

Commons Attribution-NoDerivs-NonCommercial 1.0) by the author, April

and July 2012 (German version)/December 2013 (English version)/update April 2023.

This work may be copied in noncommercial contexts if proper credit is

given to the author and IASL online.

For other permission, please contact IASL

online.

Do you want to send us your opinion or a tip? Then send us an e-mail.

Annotations

1 Davies/Harrison: Osmose 1996, chap. The Effect Osmose

Has on Participants: "They [the immersants] seemed to involve an altered

mind/body state. In this state, it seems they paradoxically feel both

disembodied (because of the visual aesthetic, being able to float and

pass through things) and embodied (due to reliance on breath and balance),

simultaneously."

On techniques of virtual realities and its use in "inclusive environments"

(see ann.6): Dinkla: Pioniere 1997, p.57-60; Grau: Art 2003, p.161-173;

Halbach: Interfaces 1994, p.170,187-214; Hattinger/Russel/Schöpf/Weibel:

Ars Electronica 1990; Heim: Realism 1998, p.98-107; Hünnekens: Betrachter

1997, p.54s.; Krueger: Reality 1991, p.65-76; Lovejoy: Currents 1997,

p.203-208. back

2 "Home of the Brain" thematises in its virtual world the discourse on virtual reality via statements of Joseph Weizenbaum, Marvin Minsky, Vilém Flusser und Paul Virilio. These four computer scientists and philosophers of media inhabit four houses arranged around a "forum". The "techno-imaginary" (see chap. IV.2.1.4.4) is articulated in a medium presenting and reflecting its own characteristics. This virtual space was used by observers with physical disabilities to realise motions being impossible under gravitational forces for visitors without disabilities (hardware: Computer von Silicon Graphics und Apple, VLP-Dataglover, Eyephone. Software: Stew, Wavefront, In-House SW). Lit.: Fleischmann: Jetztzeit 1996, p.401s.; Grau: Art 2003, p.217-231; Kluszynski: Data 2011, p.14s.,24,26,41s.,66-73. back

3 Hardware: Silicon Graphics Onyx Reality Engine, 2 personal computer ("PC clones") with 2 Crystal River Engineering Convolvotrons, Macintosh II computer with Sample Cell Audio Processing card, 2 Silicon Graphics VGX computer, NeXT computer, Virtual Research VR helmets, Sony microphones, Yamaha sound processors, sensor system "the Grippees" (developed by Steve Saunders for "Placeholder"). Programmers: Raonull Conover, Glenn Fraser, Graham Lundgren, Catherine McGinnis, Douglas McLeod, Michael Naimark, Chris Shaw, Rachel Strickland, Rob Tow, Lloyd White. Software: C, UNIX, Minimal Reality Toolkit, ALIAS animation software, TCP. Lit.: Hayles: Virtuality 1996, p.15-21; Heim: Realism 1998, p.68-72, fig.3.5-3.7; Laurel/Strickland: PlaceHolder 1994; Laurel/Strickland: Placeholder 1996; Laurel/Strickland/Tow: Placeholder 1994; Lovejoy: Currents 1997, p.204s. back

4 Observers obtain VR interfaces outside of the installation´s chamber: In the chamber the observers move with this interface in the simulations of ceiling, clouds, water, branches and plants via inhaling and exhalation, among other actions. In the virtual space these operations cause up- and downward movements. Hardware: Silicon Graphics Onix Reality Engine 2, Division DVisor HMD, Polhemus Fastrak for the measurement of head positions and the backbone gradients. A respiratory waistcoat serves for the measurement of the chest´s elongation and contraction. Animation: Georges Mauro with SOFTIMAGE 3D ("SoftImage SAAPHIRE and DKIT development libraries...SGIs Performer and GL graphics libraries." (Davies/Harrison: Osmose 1996, chap. Technical Details)). Custom Software: John Harrison. Sound: Rick Bidlack, Dorta Blaszczak with MIDI on a Macintosh computer. Localisation: Crystal River Acoustetron. Lit.: Davies/Harrison: Osmose 1996; Grau: Art 2003, p.193-201; Hansen: Bodies 2006, p.108-113,135; Heim: Realism 1998, p.162-167,171, fig.6.1-6.4; Lunenfeld: Davies 1996; Manovich: Language 2001, p.261; Paul: Digital Art 2003, p.126s. back

5 Via data helmets the observers are transfered to three places – a cave, a waterfall, a river valley – in the ennvironment of the Banff National Park in Alberta/Canada. There they appear optionally as "Spider, Snake, Fish, and Crow." (Heim: Realism 1998, p.71; Laurel/Strickland/Tow: Placeholder 1994. Cf. Hayles: Virtuality 1996, p.17). back

6 "Inclusive environments": Bricken: Worlds

1991, p.364.

"Responsive environments": see chap. II.3 with ann.14. back

7 The use of the terms "seam" and "seamless"

was inspried by Mark Chalmers´ use of the terms "seamful"

and "seamless" (Chalmers/MacColl: Design 2003). Cf. Strauss/Fleischmann:

Architektur 2003, unpaginated, chap. Das Verschwinden der Interfaces:

"The new interfaces between humans and machines can´t be taken

as barriers anymore, because they are interfaces with tendencies either

to disappear or to become invisible."

"The interface as a location of seams" ("Die Schnittstelle

als Nahtstelle"): Neitzel/Nohr: Spiel 2006, p.16. back

8 Cruz-Neira/Sandin/DeFanti: Surround-Screen 1993, p.137. Technical equipment: Cruz-Neira/Sandin/DeFanti: Surround-Screen 1993, chapter 1.3, p.136ss. Cf. Grau: Art 2003, p.3s.,238,247,299; Heim: Realism 1998, p.99-107; Kacunko: Circuit 2004, p.111,642; Robbin: Shadows 2006, p.123-127. back

9 Shaw: Movies 2002, p.271s.; Paul: Digital Art 2003, p.128s. back

10 The "internal observer" is constituted by the possibilities programmed for (external) observers being enabled by the technical interface to activate functions of the system (Dreher: Weibel 1997, p.60, ann.49). back

11 Pape: Crayoland 2002. back

12 Vgl. Heim: Realism 1998, p.98-107 on the differences between the "perceptive immersion" in "HMD VR" and the "apperceptive immersion" in "CAVE VR". back

13 At the end of "CAVE" presentations the visitors of the Ars Electronica Center in Linz received colour prints of the motifs photographed by them. Hardware: Two Silicon Graphics Onyx Reality Engines. Programmers: Patrick Bouchaud, Kimi Bishop and David Nahon. Sound: Jean-Bapiste Barrière. Lit.: Benayoun/Barrière: World 1998; Grau: Immersion 2004, p.268; Hansen: Bodies 2006, p.88-94, fig.1.8; Wilson: Information 2002, p.705ss. Thanks to Maurice Benayoun for informations about technical issues. back

[ Table of Contents| Bibliography | Next Chapter ]

[ Top | Index NetArt | NetArt Theory | Home ]