IASLonline NetArt: Theory

Thomas Dreher

History of Computer Art

IV. Images in Motion

IV.3 Evolutionary Art

- IV.3.1 Biomorphs

- IV.3.2 Evolution and Processing

- IV.3.3 Fractal Flames

- IV.3.4 Emergence

- Illustrations Part VII: Evolutionary Art: PPT / PDF

- Table of Contents

- Bibliography

- Previous Chapter

- Next Chapter

In the case of movie sequences the "synthetic realism" 1 of computer animation (see chap. IV.2.1.3 and IV.2.1.4) is a result of compositions with three-dimensional programmed objects in movable perspectival views. The animators follow visions presented in the drawings of a storyboard: Although the perspectival views of the three-dimensional elements are calculated and their transformations follow the algorithms of the animation program, these elements are reworked by the animators with an attention to details fulfilling the requirements of the drawings being parts of the storyboard.

This patchwork character use William Latham and Karl Sims (see chap. IV.3.2) in another manner than the movie animators: With the film´s storyline the cinematigraphic function of the storyboard is cancelled, too. The storyline is substituted by algorithmically structured generations of the computer animation.

From the biologic concepts of the evolution of cells and living beings Latham and Sims derive the limitations of possible generations by environmental factors. Their animation programs contain evolution possibilities and humans – the artist or observers – can replace the environmental conditions by selecting values influencing the computing processes enfolding the programmed evolution in generations. Instead of hiding the character to be composited behind cinematographic "reality effects" 2 Latham and Sims develop their three-dimensional image worlds by intervening into the programmed generation. An interplay between generative processes and artists´ interventions substitutes the interplay between biologic evolutions and environmental factors.

For their Evolutionary Art Latham and Sims found suggestions in biological research: Scientists use in theoretical biology models presenting concepts of the evolution as computer programs. The conceptualisation of the biologic evolutions´ possibilities is preferred over laboratory tests with real cells. 3

In the third chapter of "The Blind Watchmaker" (1986) Richard Dawkins presents a computer simulation of branching processes building "trees". In the case of repeated symmetric branches Dawkins reduces the amount of codes resp. the "genes" containing the elements for the branching program. "Biomorphs" with forms similar to plants and animals grow out of combinations and repetitions of these genes. 4 Dawkins takes up the term "biomorph" of the English coologist and artist Desmond Morris. As "biomorphs" Morris designated the animal-like figures of his late surrealistic paintings that were influenced by Yves Tanguy. 5

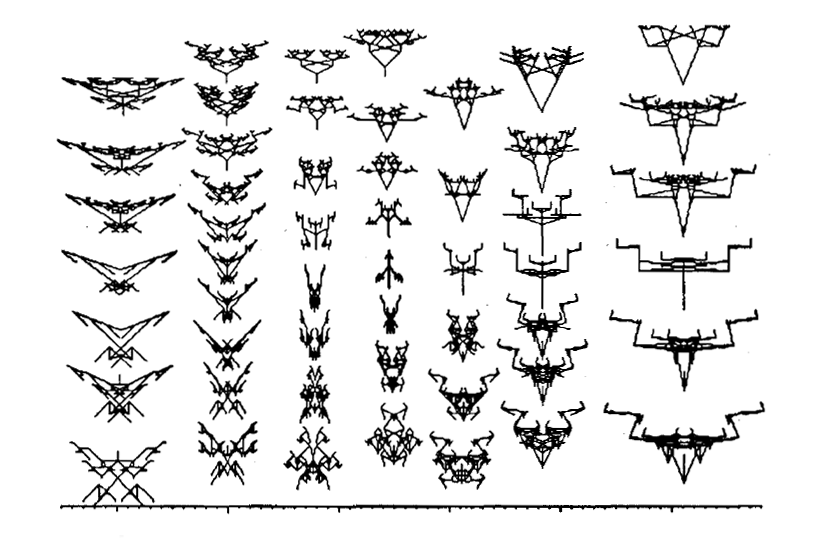

Dawkins, Richard: The Blind Watchmaker, 1986, examples of a model for the "evolution game" (Dawkins: Watchmaker 1986, p.70, fig.8).

Dawkins´ model shows the relation between genotypic codes ("genes") and phenotypic features ("biomorphs") realised by these codes in recursive procedures. The biologic developments proceed "bottom up" without a superior goal. From the "cumulative selection" 6 over generations arise context-sensitive reactions between simultaneous developments. This sensitivity is exclusively "locally determined". 7

On the one hand there is an "evolution game" with development rules contained in the "genes" producing elements that vary by mutation, on the other hand a "human selector" 8 can influence the development and is able to reduce a multilinear plurality to a certain development line. 9

Dawkins highlights the difference between an unguided development in Artificial Life and the computer games simulating worlds. He distinguishes "computer games" from "evolution games": The former are "designed by a human programmer", meanwhile in the latter case "the monsters that one encounters are undesigned and unpredictable." 10 For Dawkins "evolution games" consist of the relation between development rules and pseudo-random producing mutations.

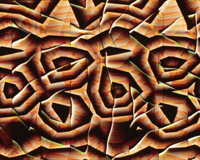

In 1992 William Latham and Stephen Todd presented their creative work on and with a program for the generation of biomorphic forms. At the IBM United Kingdom Scientific Centres in Winchester Todd developed the program for an IBM 3081 Mainframe Computer (since 1980) with IBM 5080 (since 1983) and 6090 Graphics Systems. 11 For William Latham Todd´s editors simplified the selection of three-dimensional elements and their possible combinations. The editors made it easier for Latham to concentrate himself on the best ways to use the properties of the software. The artistic selection takes place in phases and the program offers new possibilities for further creative phases. The editors offer schemes with lines marking the limits and edges of objects. Later on, colors, surface properties and shadows are added. With a "three space tracker" Latham can move the virtual object in the image space. 12

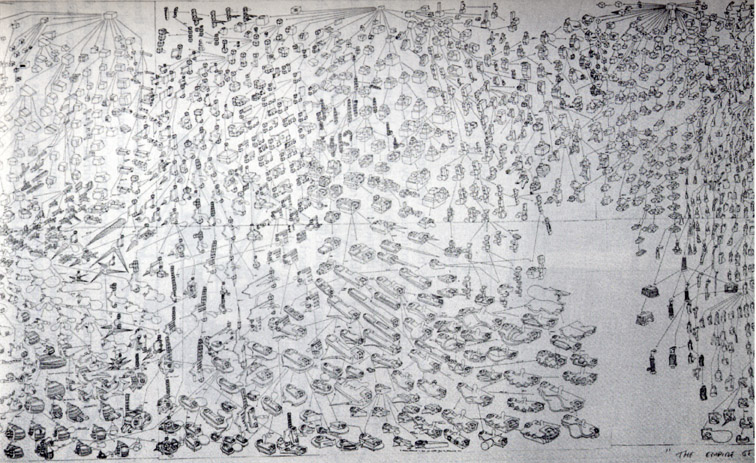

Latham, William: Form Synth, 1989, detail of a drawing, 10 meter long (Todd/Latham: Evolutionary Art 1992, p.5, fig.1.6).

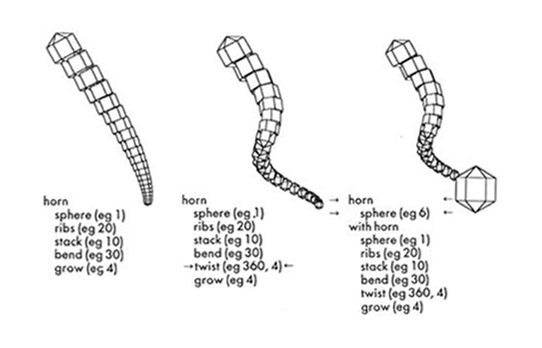

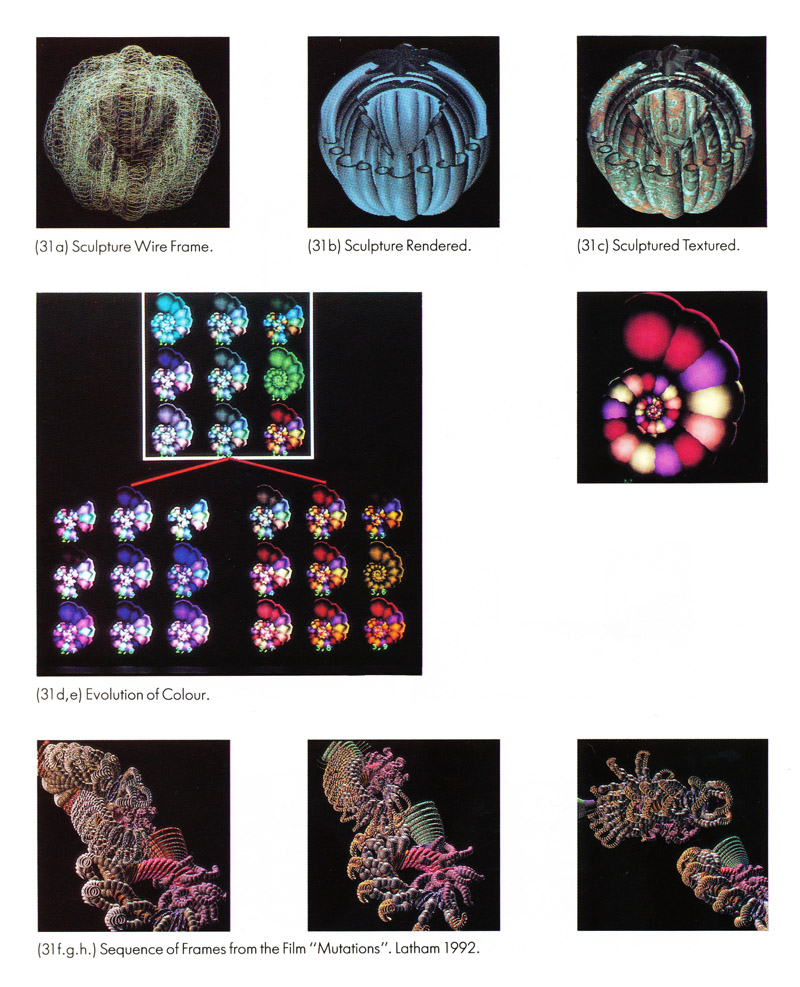

When Todd developed the software "Form Growth" with the "ESME (Extensible Solid Model Editor) programming tool" then he reconstructed characteristics of Latham´s "evolutionary trees". In 1989 Latham presented these drawings of the series "Form Synth". 13 "Form Synth" furnishes a vocabulary with three-dimensional elements being indicated by the CSG (Constructive Solid Geometry) program as line drawings. 14 There are elements that can be combined as "horns". Via input to the editor Latham can determine the quantity and the combination manner of the elements. 15 The element combinations in turn can build groups that are presented in the series "Mutations" (1991-92) in random order next to and beneath each other. "Continuous evolutions" can lead to "gene banks" for further selection phases and to animations with "life cycles" determining how long "genes" will reappear in an animation. 16

Latham, William: Horns, structure mutation with the software Mutator (Todd/Latham: Evolutionary Art 1992, p.99, fig.5.26).

Latham and Todd explain the development of their animations:

In our earliest animation, "The Conquest of Form" [1987] , the view of the rigid forms moved but the forms themselves did not change – so called `view animation´. Later in "A Sequence from the Evolution of Form" [1989] the forms metamorphosed using a technique called "gene interpolation" 17, but only a single form was visible at any one time. Our latest animation "Mutations" [1991-92] illustrates the process of a surreal evolution, involving breeding and growth, with many forms animating with complex interactions. 18

Latham, William: Mutations, film, 1992

(Todd/Latham: Evolutionary Art 1992, unpaginated, fig.31).

In Todd´s program Latham takes on the function of a "human selector" (see chap. IV.3.1). Latham describes himself as an "artist gardener" creating his "parody" of Artificial Life science by following aesthetic criteria. 19 The processing of forms in Latham´s and Todd´s "Evolutionary Art" doesn´t take care about biologic criteria. This indifference can be understood as a "parody" of the problems of the theoretical biology to design computer simulations as reconstructions of the laws of the natural cells´ development (see chap. IV.3.1). "Form Synth" already demonstrates with its selection of basic elements and their combinations that it is not a biological model. Instead it only follows sugestions by "biological forms": "Our systems...often bear no relation to biological reality." 20

Sims, Karl: Panspermia, film, 1990.

In 1990 Karl Sims presents in the short film "Panspermia" an artificial world of biological forms as an autonomous cosmos with recurring parallels to the evolution of geology and fauna on earth. For the program Particle Systems Sims finds after the short film "Particle Dreams" (1988, see chap. IV.2.1.4.1) with the artificial world of "Panspermia" a new adaptation of three-dimensional bodies in processes of de- and reconfiguration.

The film sequences show the "artificial evolution" of recurring branchings and mutations of three-dimensional elements with stem- and leaflike forms. In the framework created by Sims´ software for Thinking Machines Corporation´s Connection Machine CM-2 the human selection determines the progress of the artificial selection. From the functions offered by the program the artist chooses a sufficient complex amount. These functions determine the constructions of two-dimensional elements (x- and y-axes). To these elements a third axis (z-axis) with spatial depth is added for shading and textures.

"Genetic cross dissolves" use different properties of similar images as a basis for further evolutions. Images with different genetic origins are used to construct third images connecting both branches. External image sources can be integrated into these procedures and submitted to the general transformation processes.

Sims, Karl: Primordial Dance, film, 1991.

"Primordial Dance" (1991) features the transformation of face shapes at the end of a film with an image vocabulary being in general lesser oriented to biologic forms than "Panspermia" but more to abstract-organic forms and oriented to a design of the whole image surface. Evidently Sims is lesser interested to demonstrate 3D effects but rather to present continuously changing structures with spatial depth characteristics being generated by his program written in Lisp. In 1991 Sims explained in his article "Artificial Evolution for Computer Graphics" his programming method not without references to Richard Dawkins´ "biomorphs" and their two-dimensional branches. 21

Sims, Karl: Genetic Images, installation, Linz 1993.

This "artificial evolution" is supported by the parallel processing Connection Machine CM-2 with 32 768 processors. It was developed by the Thinking Machines Corporation, for whom Sims worked as an artist-in-residence. The installation "Genetic Images" (1993) 22 demonstrates the capabilities of this computer: 16 monitors present the evolutionary states of an image. Pressure-sensitive sensors are placed before each one of the monitors and make it possible for observers to choose the preferred state that will be the origin for the parallel processing presented on all monitors. The images on the screens change every 30 seconds. 23

Compared to Latham and Todd Sims shifts the focus of the "human selector" (see above) to the evolutions implemented by the software – the "functions" using the "genotypes" to compute the "phenotypes". 24 The "human selector" doesn´t act like a sovereign creating "gardener" (William Latham, see above) following criteria of visual perception, but as a selector of sequences provided in the system. 25

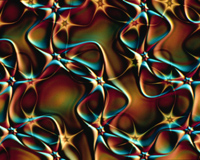

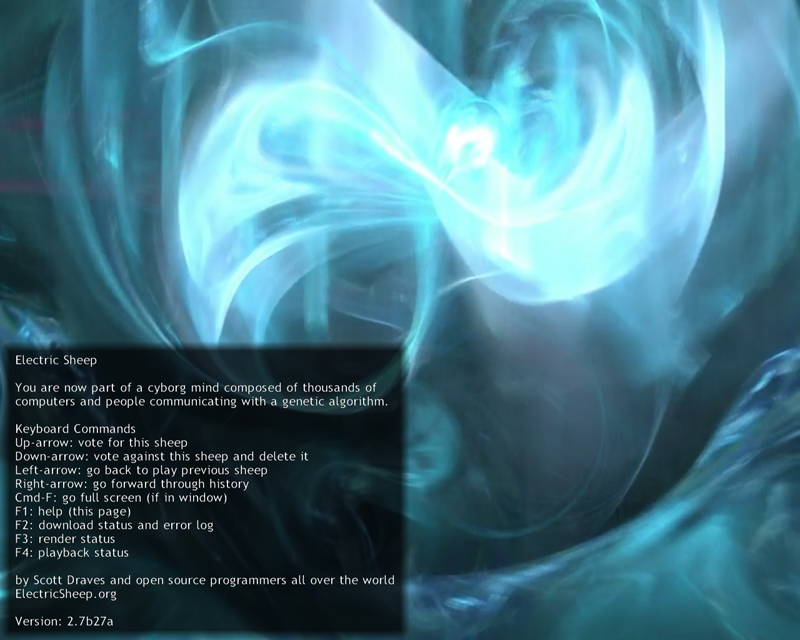

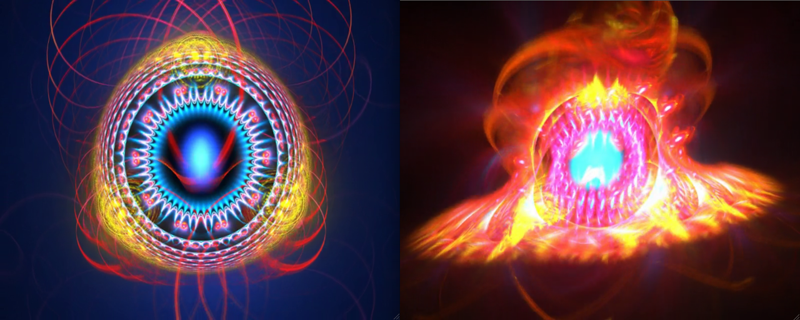

In 1991 Scott Draves developed the "Fractal Flame Algorithm" and published it in 1992 with the General Public License (GPL), that permits to develop the program further: Mark Townsend did it in 2004 by translating Draves´ program from C to Delphi Pascal for his project "Apophysis". 26 In 1999 Draves transformed his tool for image processing in the screensaver "Electric Sheep" into an ever changing animation: A network of computers generates new fractals out of elder fractals. After having installed the screensaver on their computers observers can choose fractals they like. Often selected fractals survive longer within the network and will be presented for a longer time. With the longer survival of the chosen fractals observers influence further evolutions.

"Fractal Flames" is based on repetitions of forms and generations by recursive "affine" transformations. After these linear transformations follows a further transformation phase with non-linear functions. In a third phase further affine functions generate "a post transform". The image generating process of a "flame" can be completed by a "final transform". 27

The "tone-mapping" is a "log-density mapping": During the transformation each pixel is beset several times. A "histogram" counts these fillings containing informations about the "tone-mapping". In the third transformation phase ("post-transforms") a further coordinate is added for the attribution of colours to functions. The transformations are stored in two-dimensional caches until the image generation is finished. The two-dimensional image generation provides three-dimensional optical effects. 28

Since 2001 a forth channel is added to the three colour channels. This new channel prevents a too dark presentation of dark parts of the image in the cathode ray tubes. Since 2003 the "flame" manifestations are partially rearranged by symmetry effects and thus simplified for the visual perception. 29

Draves, Scott: Electric

Sheep, internet-connected personal computers, screensaver, 1999.

Screenshot (March 2011) with user manual.

In "Electric Sheep" the computers with installed screensavers receive fractal animations from a "distributed system...with client/server architecture". Each of these "sheeps" is constituted by 128 frames and "160 floating point numbers" as its "genetic code". Observers can select preferred "sheeps" with a click on the key marked with an arrow showing upward. The lifetime, that a "sheep" can have in the system, depends from the amount of votes. Draves mentions Karl Sims (see chap.IV.3.2) as an inspiring example for the "fitness" by the observers´ choices. Draves substitutes Sims´ supercomputer by a "distributed system" built by internet-connected personal computers. 30

Draves, Scott: Electric

Sheep, internet-connected personal computers, screensaver, 1999.

Screenshots of two succesive phases (April 2012).

Since March 2004 net participants can send self-designed "genomes" via "Apophysis" to the server of "Electric Sheep". Then this server distributes the "genomes" to "all active clients" (the computers constituting "Electric Sheep´s" network). 31 The "clients" store the uploaded "sheeps". These "sheeps" are transformed by the "clients" following the "genome specifying a frame to render" received by the server. Then the "clients" send their transformations to the server. The server integrates two machines. One of them "runs the evolutionary algorithm, collects frames and votes, compresses frames, and sends genomes to clients for rendering". The other one sends the thus processed "MPEGs" via internet to computers with installed screensavers. 32

Draves, Scott: Electric

Sheep, internet-connected personal computers, screensaver, 1999.

Screenshots of two succesive phases (March-April 2012).

Draves developed with "Electric Sheep" the former Evolutionary Art for mainframe computers further into a networked system whose output can be received via screensaver and can shape the everyday life and work at personal computers: The times of computer standstills are the times of "Electric Sheep´s" screen presentation. It can become a habit during work breaks to select between transformation states of "Electric Sheep". "Electric Sheep" offers a diversion that may facilitate the return to concentrated work.

Peter Cariani differentiates in "Emergence and Artificial Life" degrees of emergence. Cariani points to Gordon Pask´s successful experiment from 1956 or 1957 with a solution of iron sulfide and electrodes giving rise to formations of iron filings that become audio sensitive. In this extreme form of emergence something new comes into being. 33 The limits of Evolutionary Art´s systems are below this extreme because their goal is not to develop capabilities to adapt themselves to environmental conditions up to self transformation but to use self contaminations by elements from different evolution lines and states (via interpolation and crossover) to construct visual structures integrating external selections by artists and observers. They restrict the system´s possibilities to generate structures out of its own resources.

Referring to Henri Focillon´s «La vie des formes» Niklas Luhmann explains in "Art as a Social System" the relationship between "system and evolution" in the "art system" as an autopoietic differentiation of forms – as "a re-entry of the form into the form". 34 In Evolutionary Art the program installed on appropriate hardware is the "system", the computing processes generate the "evolution" and when the author or observer chooses one of the interim results then he supplies the disturbance that causes reactions in the following evolutions of the system.

When Luhmann explains the "autopoiesis" in a system as its development by internal differentiations causing growing capabilities to react to external disturbances 35, then he presupposes William Ross Ashby´s "homeostasis" as a recreation of the system´s balance via self-regulation reacting to external disturbances. Ashby features in his "law of requisite variety" internal differentiations as a fundamental capability of a system to be able to react to environmental conditions resp. external disturbances. 36 Luhmann transforms Ashby´s "homeostasis" based on "requisite variety" into the "autopoiesis" of the system that includes the excluded via "re-entry" if its internal differentiation is sufficiently developed. 37

In "Art as a Social System" Luhmann defines the "communication system art" as an autonomous system defining itself by marking limits (resp. by excluding non-art) and including the heteronomous elements via "re-entry". A disturbance doesn´t cause a system´s revision but provokes decisions that can allow the system to stand the test by evolution or by exclusion of the disturbances. The observers as participants of the "communication system art" can stimulate the system´s evolution with critical contributions and provoke a shift of the border between art and the environment. 38

In Evolutionary Art the participant is integrated as a selector of forms and is then involved in the discourse on this art form as an insider, but as such he never transgresses the interface between external observation and system-internal organization.

Evolutionary Art can be considered to be a plea for autonomous art within the "communication system art". With reference to exceedable technical limits Evolutionary Art can be understood as pointing towards changeable characteristics. They offer new impulses for discourses in the "communication system art". 39 Thereby, questions concerning the self-demarcations of the system art are at disposal for new discussions.

Dr. Thomas Dreher

Schwanthalerstr. 158

D-80339 Munich

Germany.

Homepage

with numerous articles on art history since the sixties, a. o. on Concept Art and Intermedia

Art.

Copyright © (as defined in Creative

Commons Attribution-NoDerivs-NonCommercial 1.0) by the author, April

2012 (in German)/November 2013 (in English).

This work may be copied in noncommercial contexts if proper credit is

given to the author and IASL online.

For other permission, please contact IASL

online.

Do you want to send us your opinion or a tip? Then send us an e-mail.

Annotations

1 Manovich: Realism 1992. back

2 Manovich: Realism 1992. back

3 Langton: Artificial Life 1993, chap. 1, p.25ss.; Reichle: Kunst 2005, p.127,133. back

4 Dawkins: Watchmaker 1986, chap.3, p.43-74. back

5 Dawkins: Watchmaker 1986, p.55. back

6 Dawkins: Watchmaker 1986, p.45,49. back

7 Langton: Artificial Life 1993, chap. 4.2, p.40s. back

8 Dawkins: Watchmaker 1986, p.57,60. back

9 Dawkins: Watchmaker 1986, p.58, fig.4. back

10 Dawkins: Watchmaker 1986, p.60. back

11 Todd/Latham: Evolutionary Art 1992, p.167,169: Before the IBM 5080 a Vector General 3300 was used. back

12 Todd/Latham: Evolutionary Art 1992, p.170s. back

13 Todd/Latham: Evolutionary Art 1992, p.2-6,33s.,37s. back

14 Todd: Techniques 1990; Todd/Latham: Evolutionary Art 1992, p.134-137,171-180. CSG is based on the WINSOM renderer developed in 1983 by Peter Quarendon 1983. back

15 F.e. "Structure mutation": Todd/Latham: Evolutionary Art 1992, p.99ss. back

16 Todd/Latham: Evolutionary Art 1992, p.102s. back

17 Annotation: "This is usually called `parameter interpolation´, but `gene interpolation´ fits better with our terminology." (Todd/Latham: Evolutionary Art 1992, p.109) back

18 Todd/Latham: Evolutionary Art 1992, p.109. back

19 "Artist gardener": Todd/Latham: Evolutionary

Art 1992, p.12,98,207,209.

"Parody": "We create computer sculptures using a parody

of genetic engineering." (Todd/Latham: Evolutionary Art 1992, p.208).

back

20 Todd/Latham: Evolutionary Art 1992, p.40. back

21 Sims: Evolution 1991. back

22 Sims: Evolution 1993; Sims: Bilder 1993, p.404s. back

23 Whitelaw: Metacreation 2004, p.24.

On the technics of the Connection Machine: Langton: Artificial Life 1993,

chap. 7.7, p.61ss.

On the design of the Connection Machine: Thiel: Machina Cogitans 1993.

back

24 Sims: Evolution 1991, chap.2.1, 4.1. back

25 Sims: Bilder 1993. back

26 Draves/Draves: Flame 2010; Draves/Reckase: Flame 2008. back

27 Draves/Reckase: Flame 2008, p.4ss. back

28 Draves/Reckase: Flame 2008, p.9. back

29 Draves/Reckase: Flame 2008, p.11. back

30 Draves: Electric Sheep 2005. back

31 Draves: Electric Sheep 2005, PDF p.1 (April 2012: The mailing list Genetic-design can be used to send contributions realised with Fractal Flame editors to the list archive). back

32 The server is programmed with Perl, meanwhile the clients are programmed with C, C++ and Objective-C. All codes are open source (GPL. In: Draves: Electric Sheep 2005, chap.2, PDF p.2s.). back

33 Cariani: Emergence 1991, p.789. Cf. Whitelaw: Metacreation

2004, p.222s. During the experiment Gordon Pask said to Stafford Beer:

"It´s growing an ear." (Pickering: Brain 2010, p.341s.)

Definitions of "emergence": Cariani: Emergence 1991, p.775s.;

McCormack/Dorin: Art 2001, PDF p.4. back

34 Luhmann: Art 2000, p.184 with ann.34.

Luhmann´s reference to Focillon (Focillon: Vie 1934): Luhmann: Art

2000, p.109 with ann.19, p.118 with ann.34. back

35 Luhmann: Art 2000, p. 49-52, 185, 203ss., 207. back

36 See chap. II.1.5 with ann.18 on Ashby´s "homeostasis"; Luhmann: Art 2000, p.298. back

37 Porr: Systemtheorie 2002, p.12s. back

38 Dreher: Kunstwerk 2008, p.57; Luhmann: Art 2000, p.79. back

39 For observers Draves´ "Electric Sheep" can be used at work as described at the end of chap. IV.3.3 and as a provocation in discourses about the "communication system art". back

[ Table of Contents | Bibliography | Next Chapter ]

[ Top | Index NetArt | NetArt Theory | Home ]